THE ANALOG SYNTH MUSEUM

.jpg)

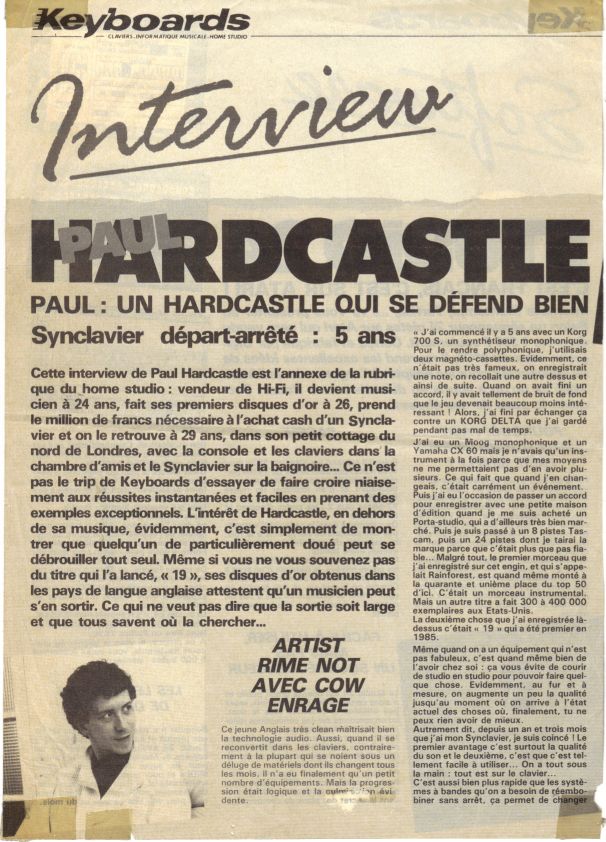

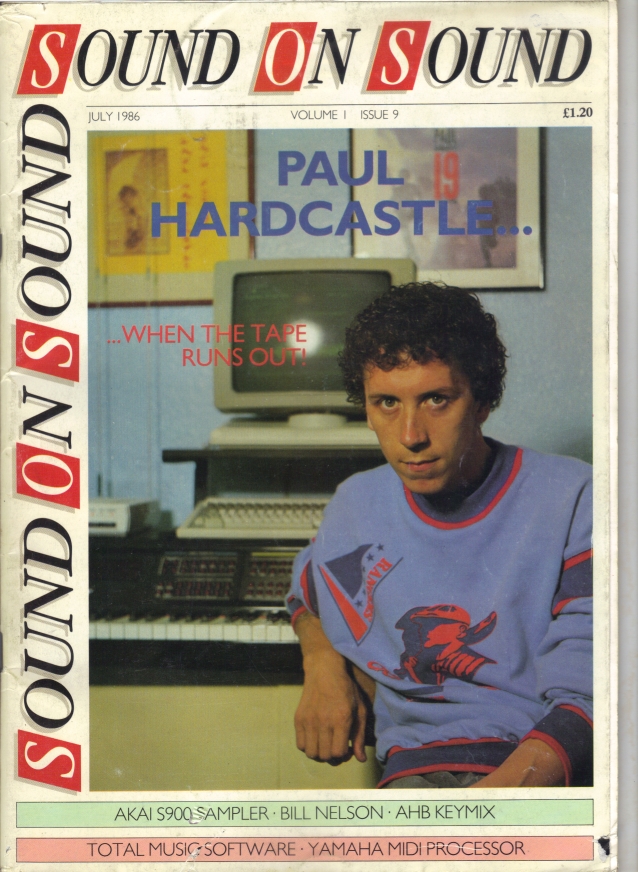

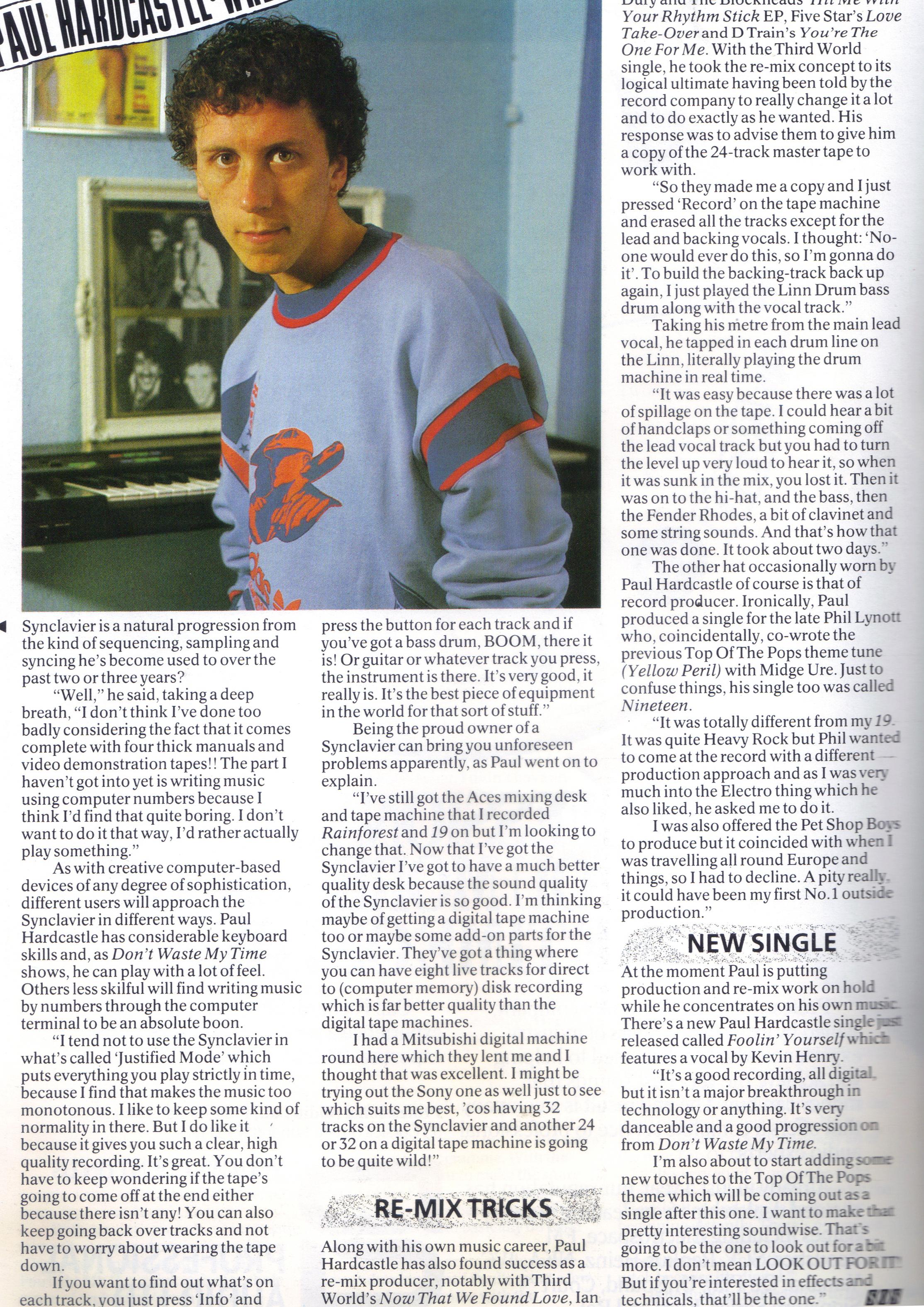

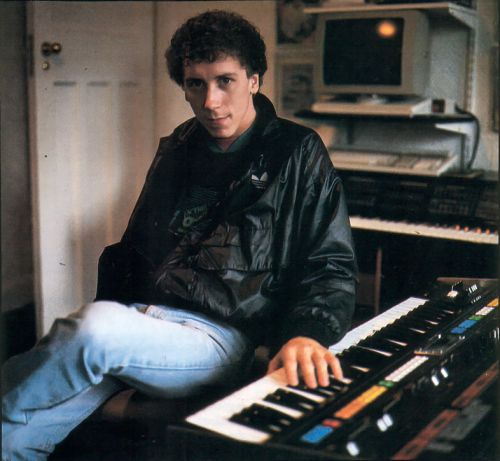

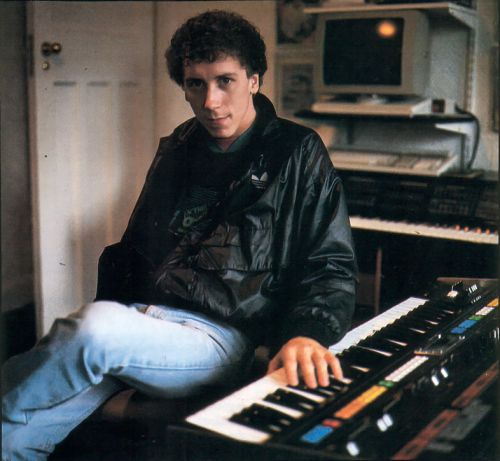

The whizz-kid that made a number one hit out of a spoken-word soundtrack and a sampler with 19' is now The Wizard, courtesy of a new signature tune for 'Top of the Pops'. Tim Goodyer meets the man, the Synclavier, and the passion for new technology.

He was a heavy metal fan, a dancefloor addict, and a mediocre keyboard player in a mediocre band. Then '19' shot Paul Hardcastle to overnight stardom, and a string of hit singles and tv signature tunes has followed.

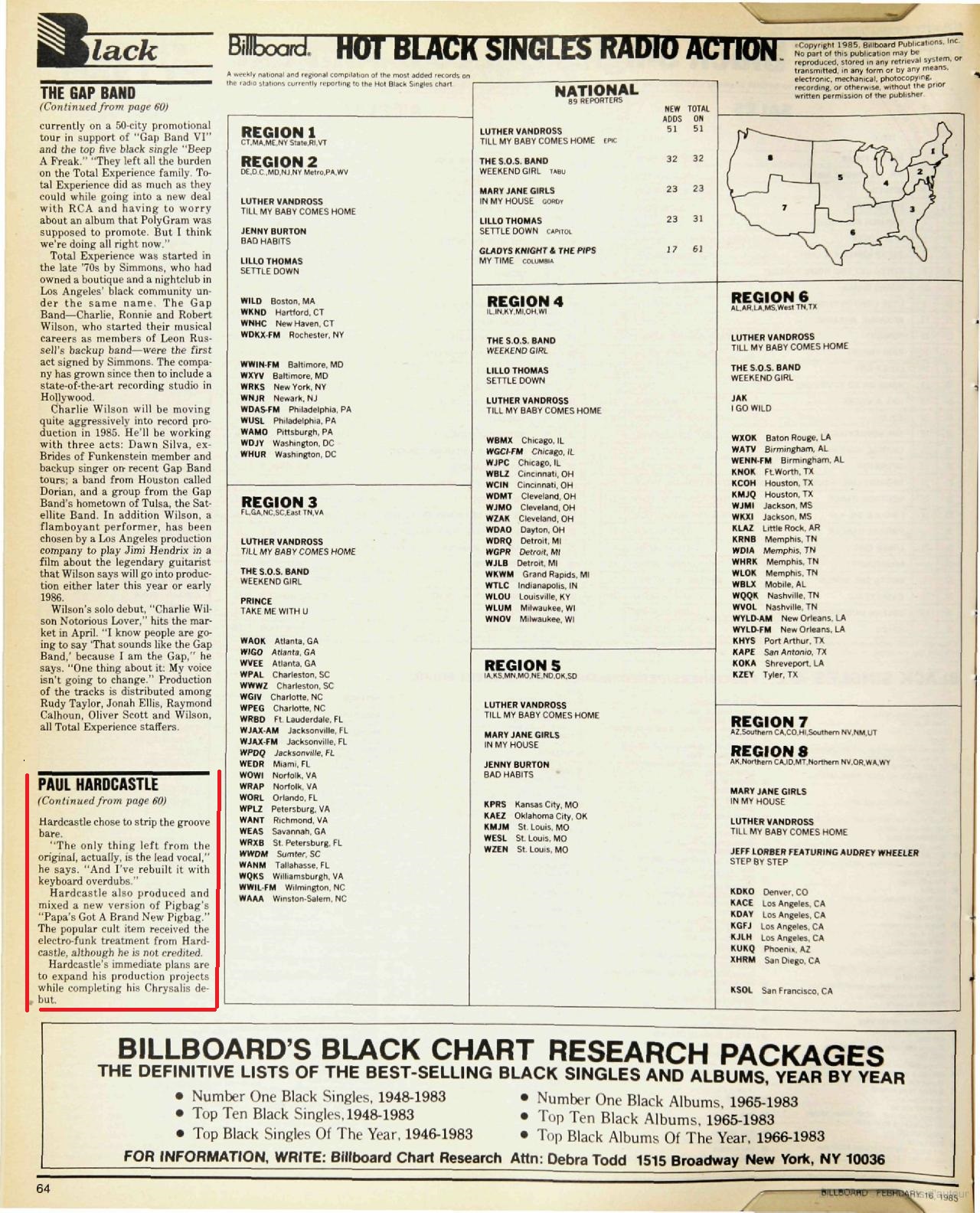

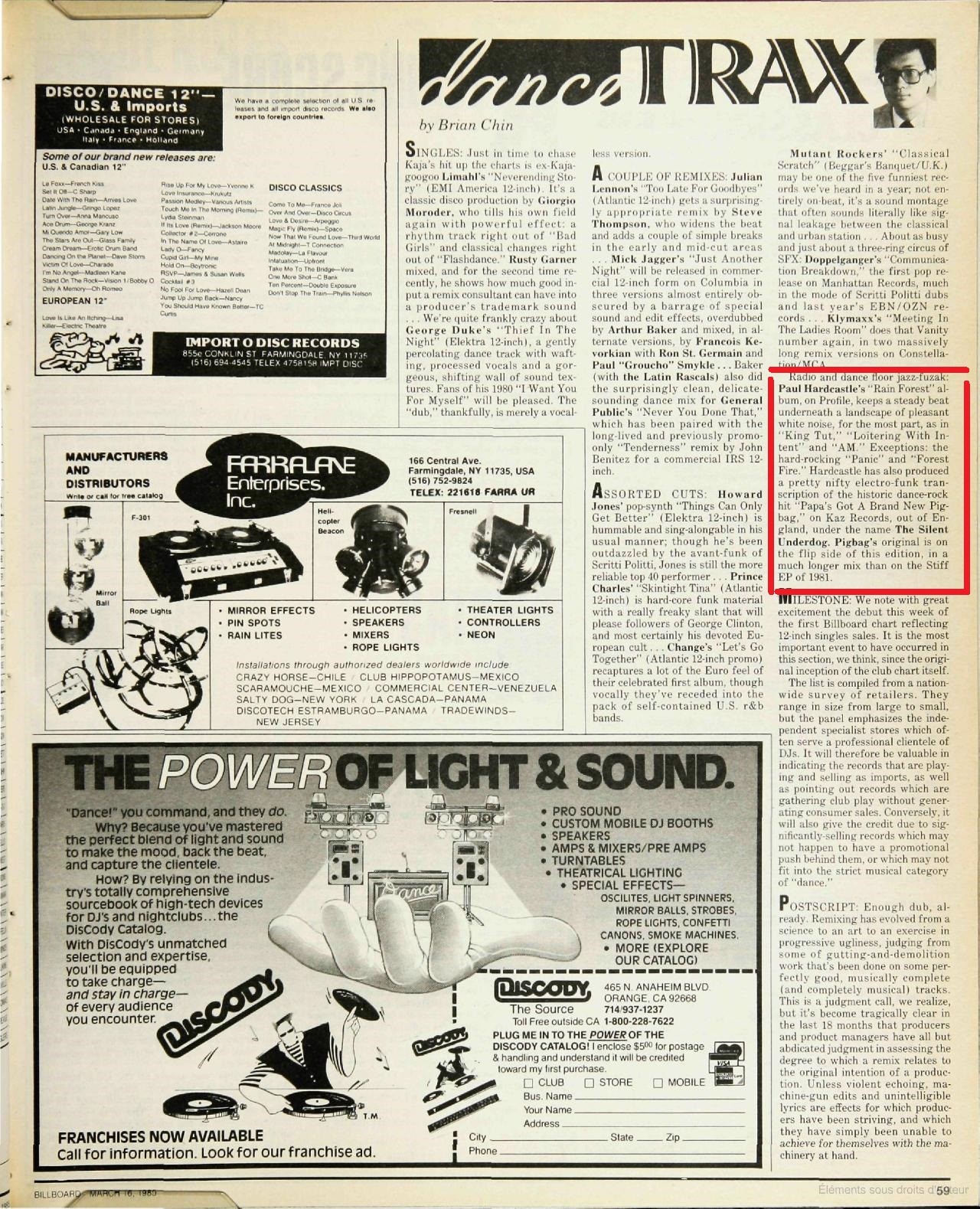

PAUL HARDCASTLE IS a busy man these days. Apart from recording a new theme tune for Top of the Pops - now released as a single, 'The Wizard' — he's been occupying himself with film work, television commercials and taking delivery of the UK's only New England Digital 16-track Direct-to-Disk recording system.

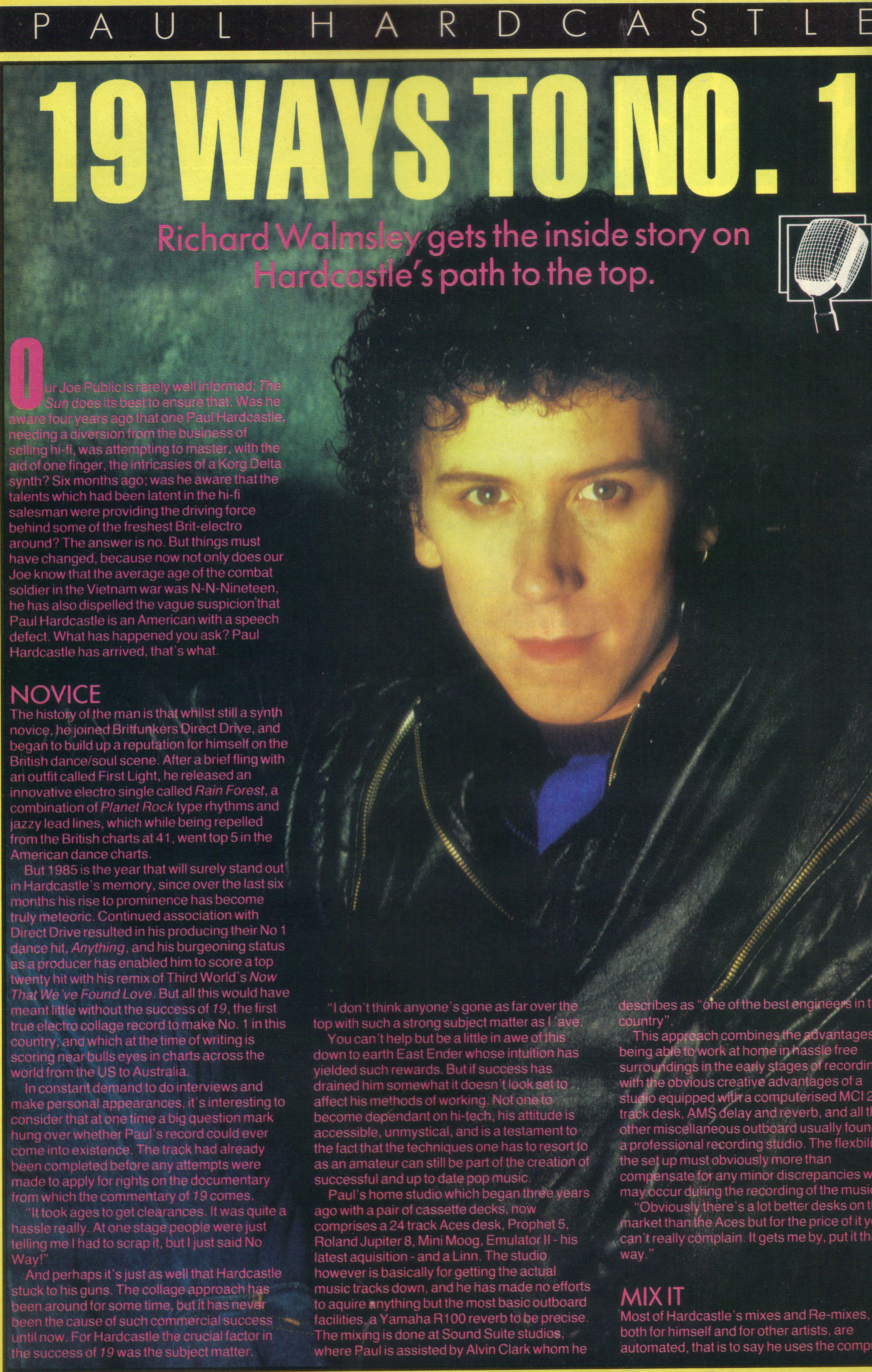

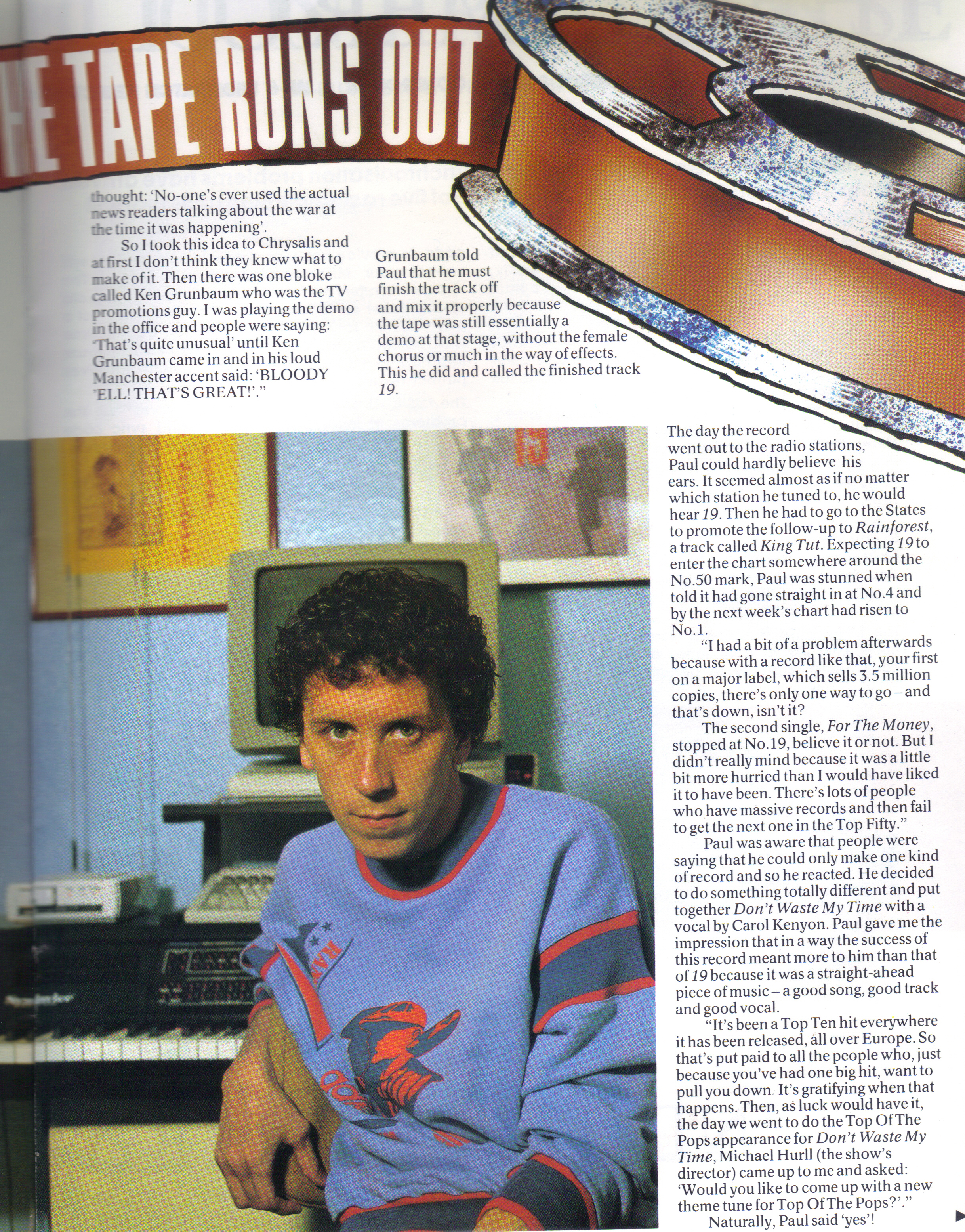

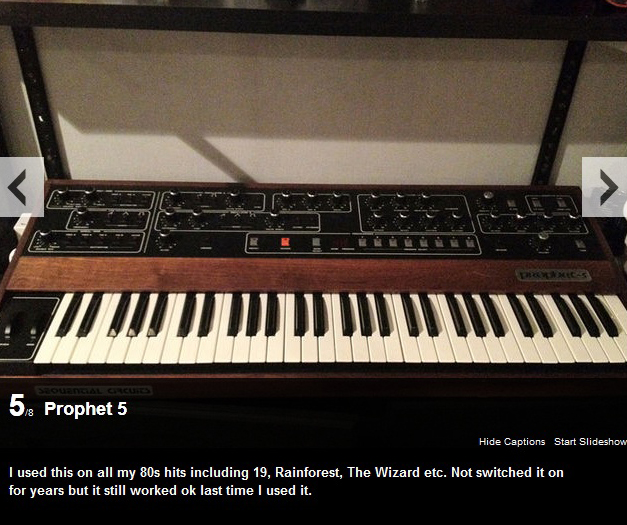

Hardcastle is best-known, internationally, as the man who made '19'. The single, released in the spring of '85, not only made his name, but also left an indelible mark on contemporary pop music and the way it's made. '19' employed a compelling dancefloor TR808 & Linndrum pattern and a strong Prophet 5 bassline, over which Hardcastle skirted round the problem of a vocal with a found-source narrative. The narration was taken from a Channel 4 documentary on the Vietnam war called 'Vietnam Requiem'. But more consequentially in musical terms, it employed one of technology's latest tricks: sampling.

Although the n-n-n-nineteen style of stuttered sample has now become a cliche, it added momentum to the growth of sampling as a technique. And the track itself remains high on Hardcastle's own playlist.

"'19' is one of the songs I still like to pull out now and again and give a listen", he admits. "I think it's still my favourite record, not because it sold, but because I can still sit down and enjoy listening to it and watching the video."

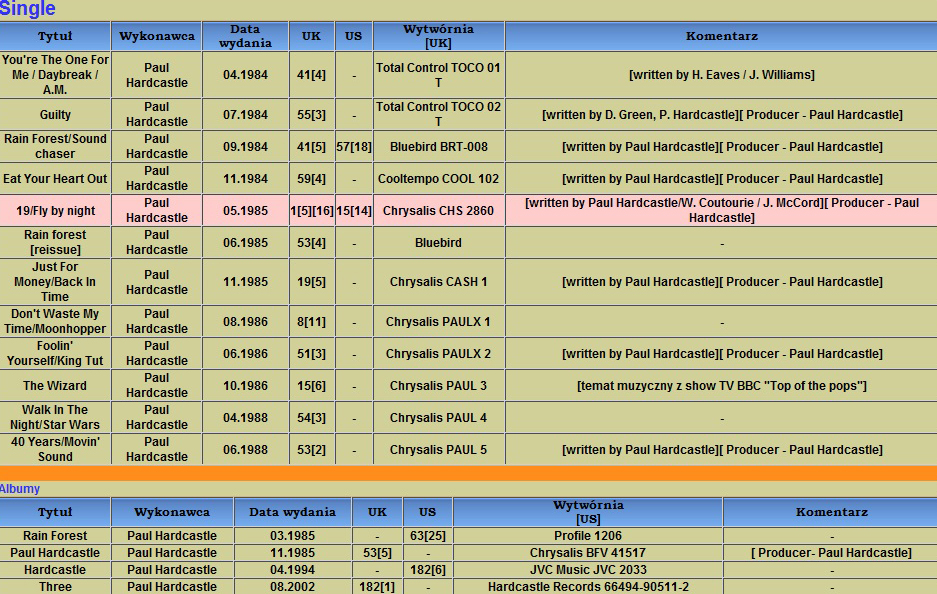

For Hardcastle, the route to '19' began with a short-lived band called Direct Drive. A couple of singles emerged, courtesy of Charlie Gillett's Oval label.

"I started playing around the end of '81 with an old Korg 700", Hardcastle recalls. "I was into dance stuff at the time but before that I'd been listening to Hawkwind, Black Sabbath and Deep Purple. I saw this ad for a keyboard player in Melody Maker and went up for it. I really was the pits then, but I'd put some things down on tape and they liked my ideas and my approach, so I got the job.

"I stayed with them for seven or eight months, then myself and the singer split and we became a group called First Light. We had a couple of singles out on London Records, and that was when I started getting into instrumentals. I was doing all the B-sides to the singles on my own, and they were getting more attention than the A-sides."

A dispute with London resulted in the formation of Hardcastle's own Total Control label...

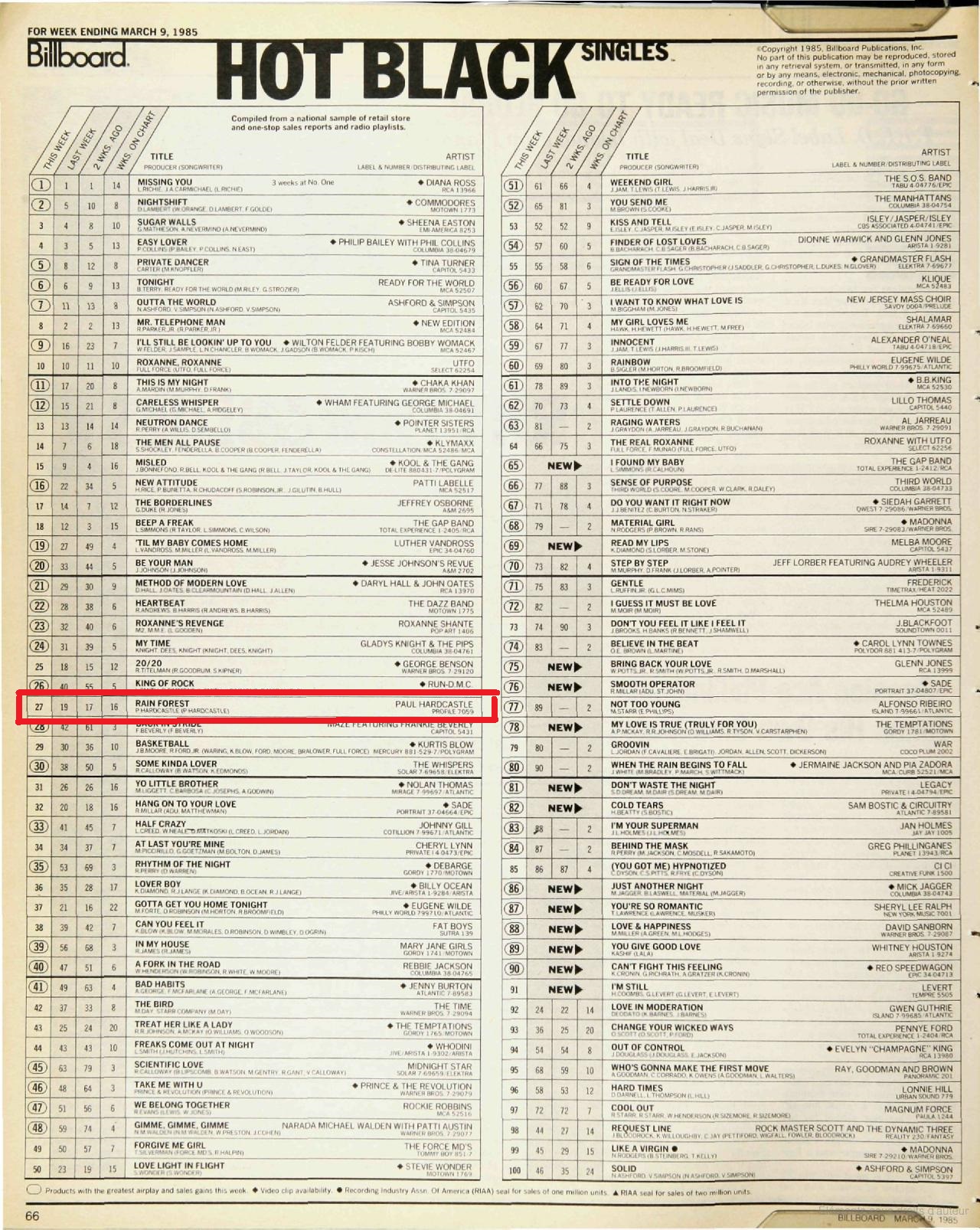

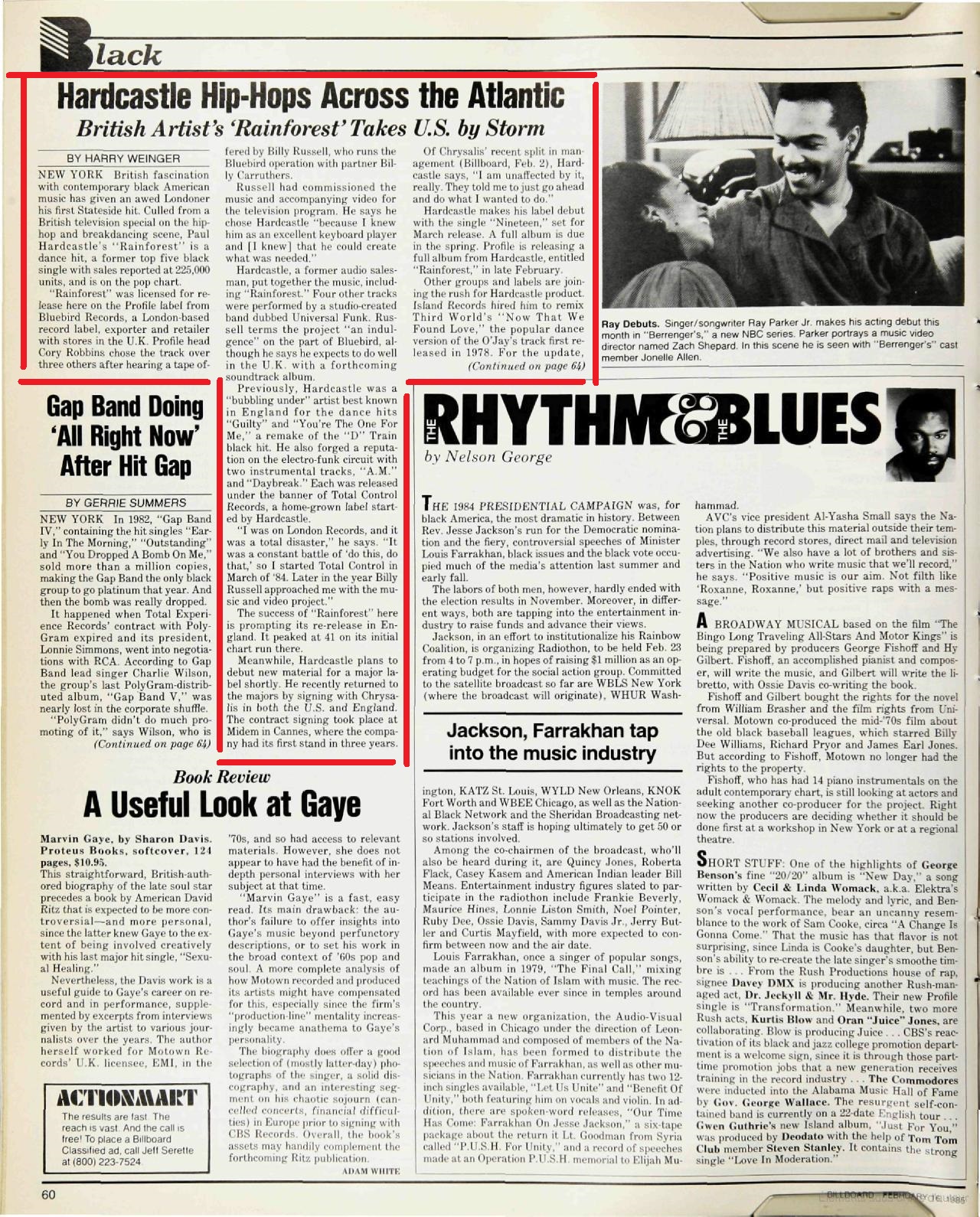

"The first single we put out was a cover of D-Train's 'You're The One For Me' which got to 41 in the national charts — and that was only bad luck due to poor distribution. I then put out a record called 'Rainforest' on Bluebird which, again, stopped at 41, one place away from getting at least five Radio 1 airplays."

By this time, Hardcastle had become an attractive enough proposition for the Chrysalis label to approach him. In contrast with the unhappy association with London, he found the attitudes at Chrysalis much more to his liking - and to his advantage.

"I took them '19' and said: 'there's my single!' One bloke there raved about it and it was through his enthusiasm that everyone got behind it. They released it and suddenly it was everywhere. I don't think they really took it all in until it was over. It went to number one here, and we had 13 number ones in all. The only place it didn't make it was Italy, where it stayed at number two for five weeks — I still don't know which bastard kept it off."

"I took Chrysalis '19' and said: 'There's my single!' One bloke there raved about it and it was through his enthusiasm that everyone got behind it. They released it and suddenly it was everywhere. I don't think they took it all in until it was over."

THREE-AND-A-HALF MILLION single sales later, Hardcastle had to face one of the oldest dilemmas in pop: how to follow a successful single. The '19' man needed advice, but ended up getting too much of it.

"It was like 'now your next record is going to be...' In the end I was trying to accommodate everyone, but I'd never do that again. You think you don't want to upset the record company, but that's rubbish because you just upset yourself instead. I think I'd rather upset the record company. One thing I stand for now is doing exactly what I want. Obviously I can't start making ten-minute singles, but as to what's in them, that's mine."

The chosen sequel to '19' was 'Just For Money', a musical look at the Great Train Robbery and the St Valentine's Day Massacre that drew on the talents of actors Laurence Olivier and Bob Hoskins for its narrative. It was a more conventional single than '19', but its successor, 'Don't Waste My Time', was more conventional still. Yes, it was actually a song, with singer (as opposed to narrator or actor) Carol Kenyon standing under the vocal spotlight.

Both singles sold well, but neither created the same excitement as '19'. Their creator, though, has a wider overall view of his activities, and isn't overly concerned that he hasn't been able, as yet, to equal the success of the Vietnam cameo.

"I never really saw myself as being like Five Star, who have to have a record out every five weeks or something. I like my singles to be a little bit special or a little bit different. Although I'm not berserk on the band, you have a feeling it's an event when a Frankie Goes To Hollywood single comes out. It's not like a conveyor belt.

"'Just For Money' was a bit of a mistake because you need to see the video to appreciate it. If the video had been shown it would have been a massive hit. Everyone who's seen the video says they've totally changed their opinion of it. Making that so dependent on the video was a mistake, but I saw it as a visual thing then. We've won an award for the video, but you can't win 'em all, can you?

"I think people were expecting a lot more of the same sort of stuff as '19', and I was being told not to do the same sort of thing because everyone was expecting it. You can never please everyone.

"When I made 'Don't Waste My Time', although it was a hit people from Radio 1 said 'you're not as adventurous as you used to be, are you?'. Then there were the people who bought 'Don't Waste My Time' saying 'I'm glad you didn't do another weird record'. You're in the middle and you have to make your own mind up — that's the only way to do things.

"I've also been doing a few tracks for films, a couple of commercials, remixes and production work for other people — just exploring different areas. I know I'm classed as dance-based but I've produced records for Phil Lynott and Ian Dury. I don't hold myself in one category. Music-wise I make hard driving beat records, but that doesn't influence what I do with other people's records.

"I'll be happier when I know how to use the Direct-to-Disk. I hate sitting down with the manual; I just want to get up and press buttons and see what happens. Sometimes I've been pressing the wrong buttons and it's been saying 'Read Error' and all that rubbish."

"On Third World's remix I just went into the studio and put all the tracks into Record except the lead vocal. After that I became very good at playing LinnDrum hi-hats, bass and snare live, because all I had to go on was the spill on the lead vocal track!"

Extremes have played a large part in Hardcastle's work, and his acquisition of the Direct-to-Disk system being the latest — and most expensive — example. But such luxuries weren't always the status quo, as Hardcastle is quick to point out.

"I recorded '19' on what must have been the cheapest 24-track system in the world; that was the Aces setup. It cost me about ten grand when I bought it and it was the first thing I saved up for ages to get. I'd had it for about three days when I recorded this little instrumental called 'Rainforest' which went on to sell about 350,000 copies in America. After 'Rainforest' I did the album, and that's done pretty well. Then I recorded '19' on it. It's funny because you can knock it and say it's the cheapest in the world, but then my Ivor Novello award says I sold more singles than anyone else internationally in 1985.

"So it's not all about technology. But, when you get into recording, you always want to go up and up. It's like a bug, a dangerous drug. A hit like '19' helps a lot, but I've ploughed most of the money from that back in now. It's always been my dream to have an extremely good studio setup."

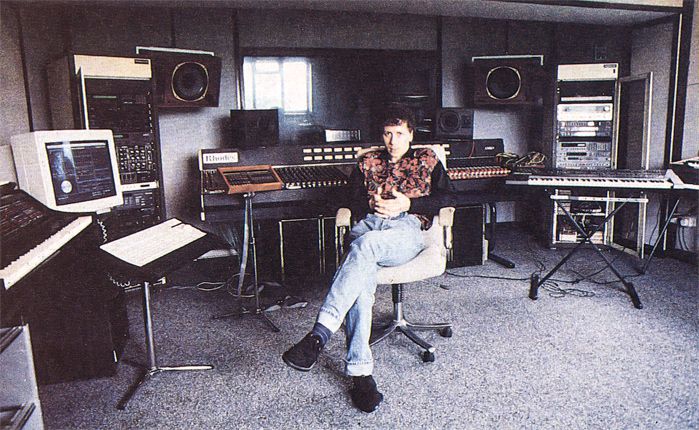

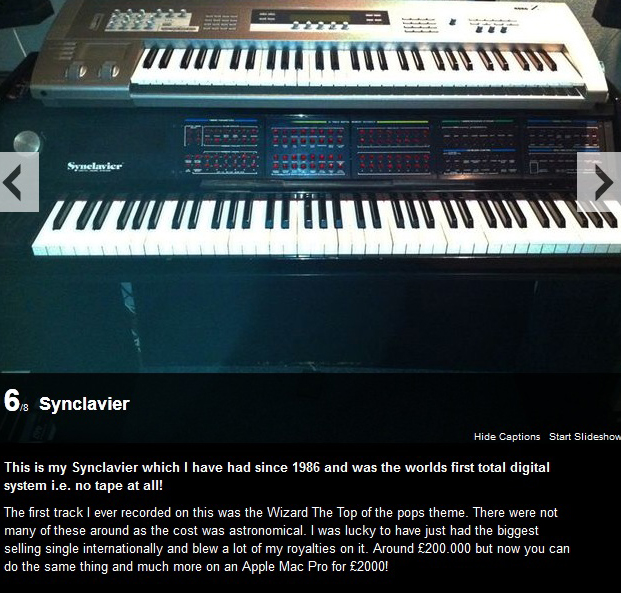

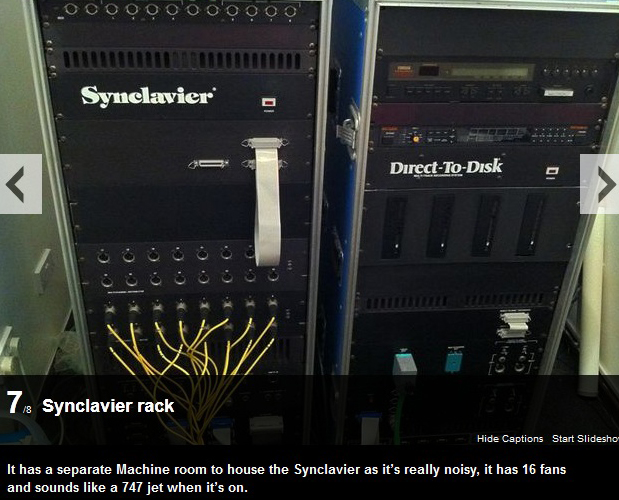

UNCHARACTERISTIC THOUGH IT may be, this understatement leads Hardcastle onto what is obviously his current passion. The arrival of the Direct-to-Disk system itself was pre-empted by the more common Synclavier system which, by his own admission, took a while to get used to. Now the painful learning process is about to be repeated, and it seems unlikely there'll be a users' group to compare notes with...

"I've had a guy from New England Digital in for about three weeks installing it and getting things to go right. This is the only 16-track that's been ordered in this country. It went out at the same time as Pat Metheny's in America, but Sting is supposed to be getting a four-track version."

The Direct-to-Disk system is designed to replace the multitrack tape stage of recording, using Winchester disks to store a digital representation of analogue signals.

"It's not a glorified sequencer", Hardcastle stresses. "It's a live recorder. The easiest way to describe it is like having 16 Compact Discs, but all with the ability to record, and all with twice the sampling frequency of CD. And even if I sample at half the maximum sampling rate, it's still clearer than Compact Disc.

"I do all the drum programming from the Synclavier now. It's 20 times easier and I can do a lot more with the sounds-like adding dynamics, taking an 808 cowbell and chorusing it, or putting it at an octave or a fifth to the original sample."

"The tracks are 13½ minutes long each, but one of the best parts of it is that you can go straight back into play after recording without rewinding, because it's random access memory. I had a sax player over here helping me beef up the Late, Late Breakfast Show theme, and he couldn't believe that he'd just played his part and I was playing it straight back to him. That's only normally possible with a sequencer."

It's no surprise, then, to learn that Hardcastle rarely has any use for two-inch or quarter-inch tape any more.

"I master straight onto a Sony PCM F1. The only problem with that is you can't edit on it. If I do need to do some edits I can still go across to the Revox without too much loss in quality because it's all been put down so clean. It's usually at the 24-track stage that you manage to build up a lot of noise. If there's none there in the first place, you find it doesn't really hurt at all to bounce onto analogue.

"There are 16 stereo tracks on the Direct-to-Disk, not 16 mono tracks. It's like a 32-track recorder because all the things you'd normally want to do in stereo you can do without losing another track. The voices on the Synclavier are all stereo too, and now the sampling's stereo. What New England Digital tend to do is put a lot of facilities on a machine, and then work on the software for a particular area at a time. There are buttons that aren't in use yet like the Chain, Insert and Delete functions. Very soon I'll be able to write a verse and a chorus into the Synclavier and, if I want to try taking one part out and putting it somewhere else, I'll be able to do that like you can on the LinnDrum.

"The Direct-to-Disk uses cartridges to download all the information when you get to the end of the 13½ minutes. There's such an amount of memory to take off - 13½ minutes recorded at that sort of quality takes up around 156 Megabytes of memory. Think how long it takes a micro to load up a program from cassette, and remember that's only around 64K. This is 156 million bytes. I've only used it once so far, though, and that was for the Late, Late Breakfast Show.

"It's the most advanced recording technology in the world, and it's going to take people a long time to catch up with that. Now NED are going into the video post-production market."

With so much exciting new technology to occupy him, Paul Hardcastle can only be a happy man...

"I'll be happier when I know how to use it! I hate sitting down with the manual, I just want to get up and press buttons and see what happens. Sometimes I've been pressing the wrong buttons and it's been saying 'Read Error' and all that rubbish... There's so much you can do that I'm learning new things every day."

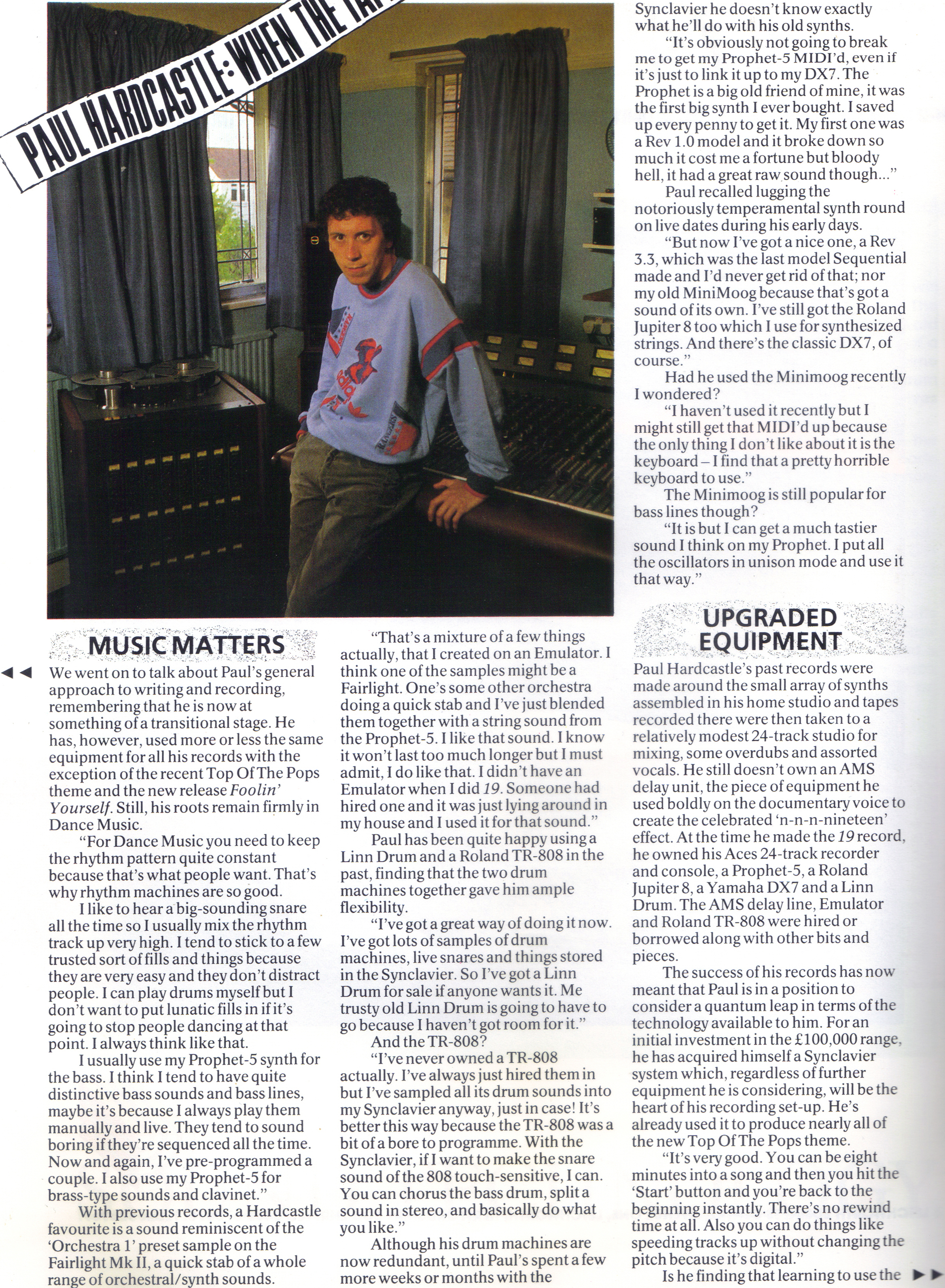

Moving on to the subject of songwriting, Hardcastle seems unable to pinpoint the approach that's given him a string of charting singles. There's no rigid formula he can define that's been responsible for his success, though it quickly becomes clear that without technology, life would be a good deal more difficult.

"You like the sound of what you're doing and you tend to leave it unchanged for a while. But then there comes a time when you say: 'Hang on, I've been doing this type of thing for quite a long time now', and then it's time to make a change."

"I write every way, I mean every way. The '19' thing started with the TV programme off a video. 'Just For Money' was when I was thinking about the Great Train Robbery for some reason. I get ideas from lyrics, rhythm tracks, chords, riffs, any little thing that you might think of.

"My songs have been put together in totally different ways. I used to work with Steve Levine and we both agreed that you can go into the studio and just get a sound, like making a Rhodes sound really big and chorusy, and it will sound so great that it sounds like a hit on its own. It sounds silly but it can give you inspiration like a guitarist with an amp; take half the heavy metal guitar players and take their amps away from them, and they won't have half the inspiration to start doing these 20-year-long solos. I like long guitar solos so I'm not criticising that, but I couldn't come up with bass riffs on a Casio, or a DX7 for that matter, because I don't find them very inspiring. Give me the Prophet or the MiniMoog and it's a totally different thing."

And speaking of inspiring sounds, those TR808 drum noises must have been one of the crucial elements behind '19's beguiling appeal. Yet the machine itself is now redundant, as Hardcastle uses its sounds as part of a library of percussion voices that issue from his Synclavier.

"I do all the drum programming from the Synclavier now", he says. "Number one: it's 20 times easier; the 808 is the worst drum machine in the world to program. Number two: I can do a lot more with the sounds — I can add dynamics, I can take an 808 cowbell and chorus it within the Synclavier. When you do that, it automatically duplicates that voice. Then I can put it at an octave or a fifth to the original sample.

"I tend to use a bass drum from the 808, a snare from the Linn plus a sample, a hi-hat from the 707, handclaps from the 808 and 707... I've got a whole page of drum machine sounds and a live kit as well.

"If I'm using the sequencer for putting down the drums and I don't like the sound of the bass drum, I can replace it with another one. If it's on track one I can just replace, say, a LinnDrum bass drum with a TR707 bass drum, and that's fantastic.

"I can substitute anything across. If I've got a synthesiser chord riff playing I can drop a guitar sample in instead to see what it'd sound like with a guitar. A lot of the things I'm doing now start off one way and then totally change. I've done a remix of 'The Wizard' that I haven't made electronic; it's more acoustic.

"You find you like the sound of what you're doing and you tend to leave it unchanged for a while. But then there comes a time when you say: 'hang on, I've been doing this type of thing for quite a long time now' and then it's time to make a change. Not a small change like just leaving the cowbell out, but 'Whack!' — change over the lot.

"So now I'm using sampled acoustic drums a lot because I think people are starting to get a bit fed up with LinnDrums and things. What I used to do with the 808 was not take a lot of time or care programming it, but I don't think it makes a lot of difference with an 808 because it's a synthetic drum machine. I used to find the LinnDrum was awful for triplet bass drums, but grab an 808 and suddenly there it is."

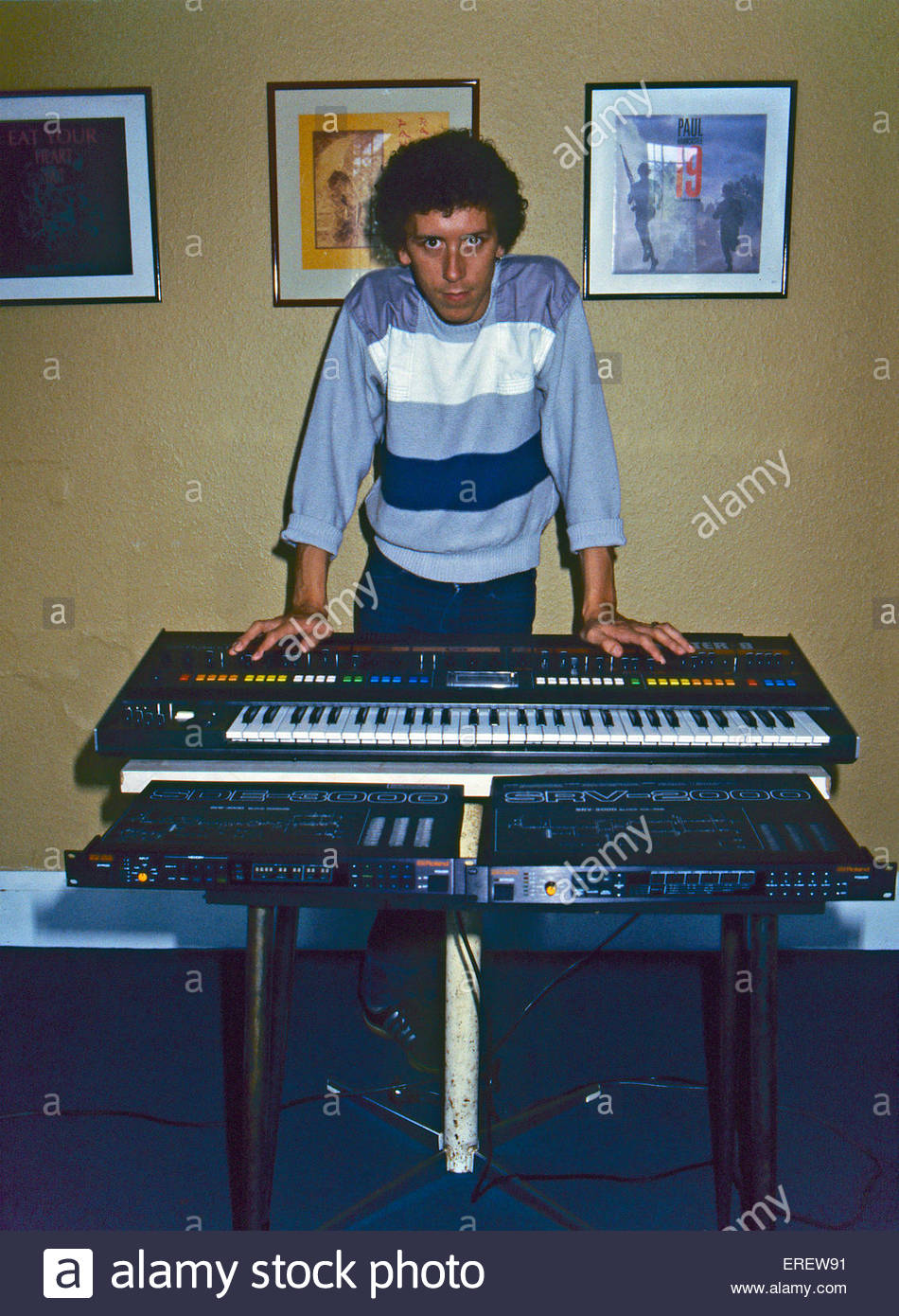

But if anything were capable of being all things to all men Quentin Crisp would have a patent on it by now, and so it is that even a Synclavier has its shortcomings. As a result, it sits in Hardcastle's East London studio with a selection of more modest synthesisers for company.

"The one thing the Synclavier really falls down on is piano sounds", Hardcastle admits. "But I love the DX Rhodes — I took the original preset, 11 I think, and fiddled about until I got a little more top on it.

"I've also got a Roland Jupiter 8, the trusted Prophet 5, which to me is still the best analogue synth that's ever been built, and a MiniMoog, or part of a MiniMoog anyway — I got rid of that horrible keyboard, and now I play it from the Synclavier or DX7. A friend of mine from a studio called Soundsuite who builds the UMI converter built one for me.

"And I got one of the new Korg DVP1 vocoders recently, though I haven't used it properly yet. Other things have been put to one side lately to make way for the Direct-to-Disk unit, but when I've got it all sussed I'll have a bit more time to sort things out."

"And I got one of the new Korg DVP1 vocoders recently, though I haven't used it properly yet. Other things have been put to one side lately to make way for the Direct-to-Disk unit, but when I've got it all sussed I'll have a bit more time to sort things out."

It'll be interesting to see what future innovation deposes the Synclavier from its throne, and captures the imagination of one of music technology's most talented — and down-to-earth — Wizards.

studio: Paul Hardcastle

Hi, I'm Paul Hardcastle and this is my studio, it's been up and running since 1987 and it's mostly used by me, my daughter Maxine and my son Paul Jnr.

Paul Jnr is a sax player and has been working on tracks for Pacha as has Maxine, in fact we all have, my Pacha album came out just last month, Perceptions Of Pacha 8. I recorded the Sound track to the spice girls movie Spice world, for which I won best score award. What's nice is that it has a great view over the fields of Essex, and is not just 4 walls - well the Vocal room is but hey I'm not a vocalist so I don't go in there much!

Lately I have recorded all of my New album '19 Below Zero' in the Studio, which I have done for Universal Music, released on October 15th, it took around a year to put together and used the equipment as seen in the following pictures.

What was amazing was that in the loft while looking for some Midi leads, I came across an old 24 track master which I thought had been misplaced for good, it had an alternative version on 19 that I did at the same time as the original, so I bounced to Aiff files, remixed and added new sounds to it. It's called 19 Below Zero and is the last track on the Album, this Mix has ever been heard before, Rob da Bank also recorded a mix of 19 for the new album.

ANALOGSYNTHMUSEUM; 2011