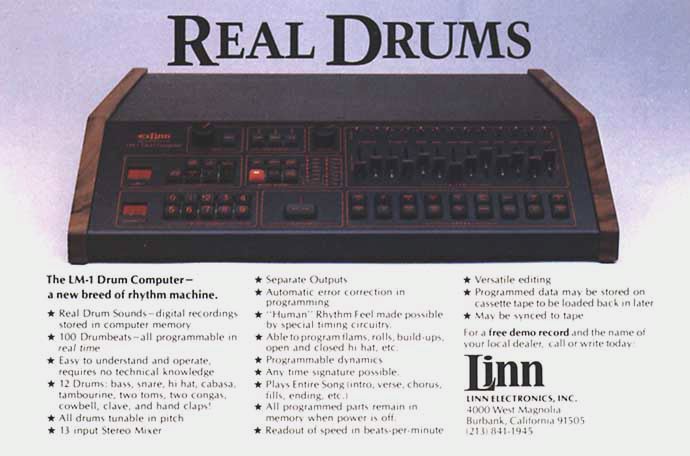

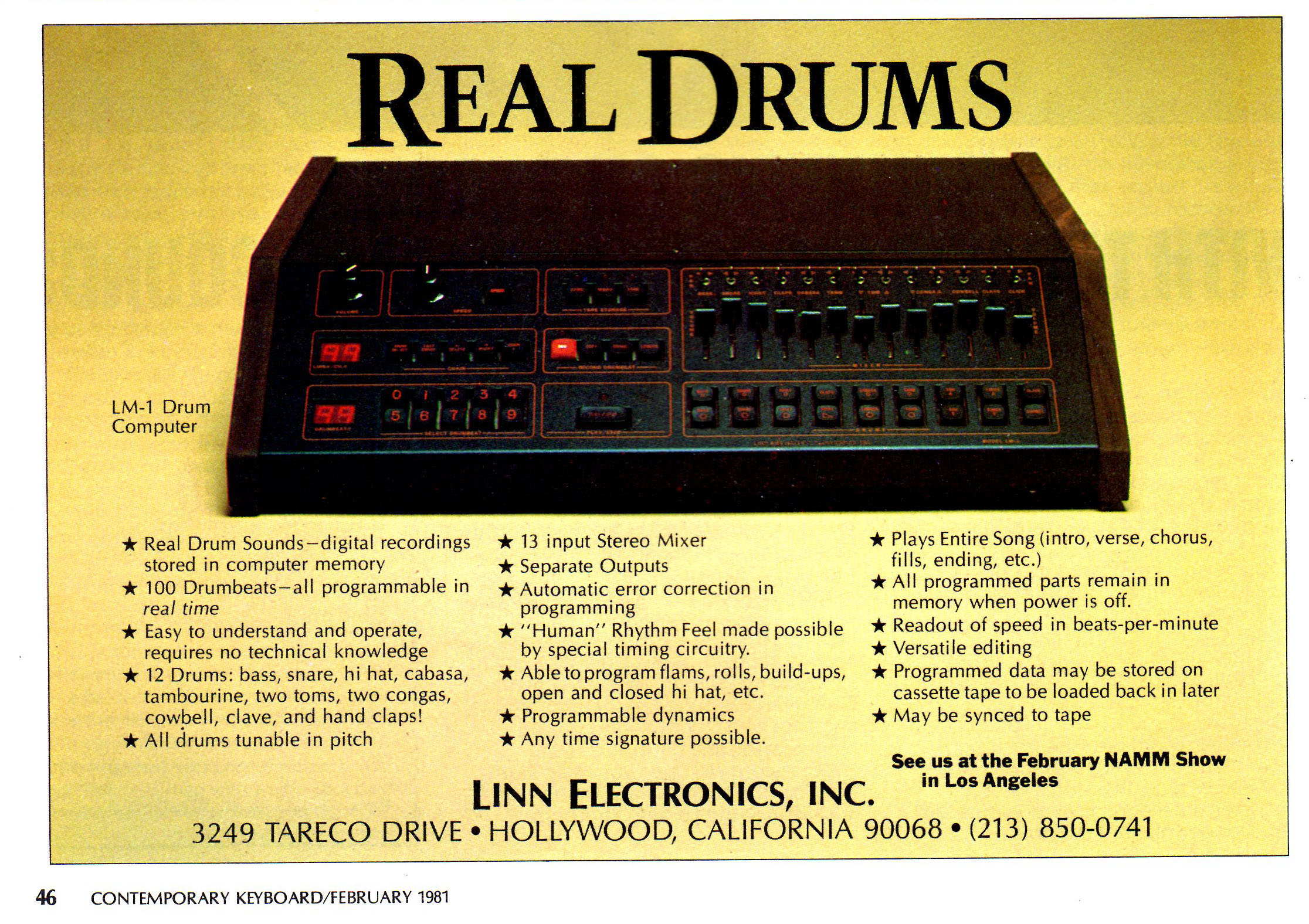

This is THE classic drum machine of the 80's - it launched the drum machine revolution! The Linn LM-1 Drum Computer was created by guitarist Roger Linn and he used samples of acoustic drum sounds. At the time, they sounded great and much more realistic and they were a fresh alternative to the analog drum sounds of the '80's drum machines. About 500 LM-1's were made before the LinnDrum model appeared in 1982.

There are twelve 28kHz samples including: snare, kick, three toms, close & open hat, tambourine, congas, claps, cowbell, Clave (early revision) rimshot (last revision), but no ride or crash. There are also 100 memory patches! Patterns can be created in real or step time. An innovations of the time was the swing and quantize functions that appeared on the LM-1. The LM-1 is an historical synth that has a place in the sound of music from the heart of the '80's. Only 500 of these things are out there so don't count on finding one easily. It has been used by Phil Collins, Thompson Twins, Stevie Wonder, Gary Numan, Depeche Mode, The Human League, Jean-Michel Jarre, Vangelis, John Carpenter, Todd Rundgren, Prince, and The Art of Noise.

Polyphony - 12 sounds

Samples - 28kHz Samples: bass, snare, rimshot or clave, hihat, 3 toms, cabasa, tambourine, high and low congas, cowbell, claps.

Patterns - 100

Songs - 8 of 99 patterns

New & Cool Functions - Quantizing, real-time programming and digital metronome

Control - Tape sync and out Clock

Date Produced - 1980-83

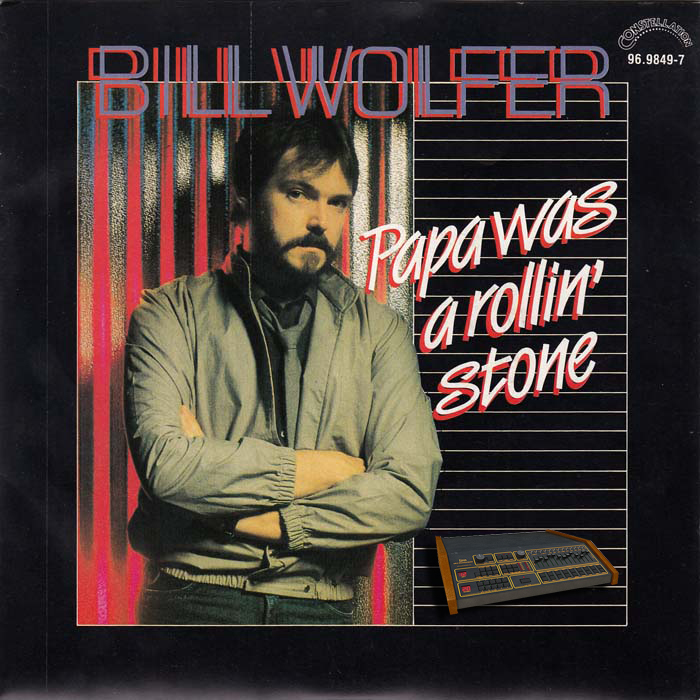

Piano [Acoustic], Electric Piano [Rhodes], Synthesizer [Cs-80], Synthesizer [Mini-moog], Synthesizer [Micro Moog], Synthesizer [Prophet 5], Electronic Drums [Linn LM-1 Drumcomputer], Effects [Vocoder], Electric Piano [Arp 16-voice] – Bill Wolfer Producer, Arranged By, Programmed By [Synthesizer] – Bill Wolfer

Herbie Hancock's Keyboards [Emu Polyphonic Keyboard, Clavitar], Synthesizer [Waves Minimoog, Minimoog, Prophet 5, Oberheim 8 Voice, Yamaha Cs-80, Arp 2600], Clavinet [Hohner], Electric Piano [Rhodes 88 Suitcase Piano], Vocoder [Sennheiser], Synthesizer [Linn LM-1 Drum Computer], Computer [Modified Apple Ii Plus Microcomputer], Piano.

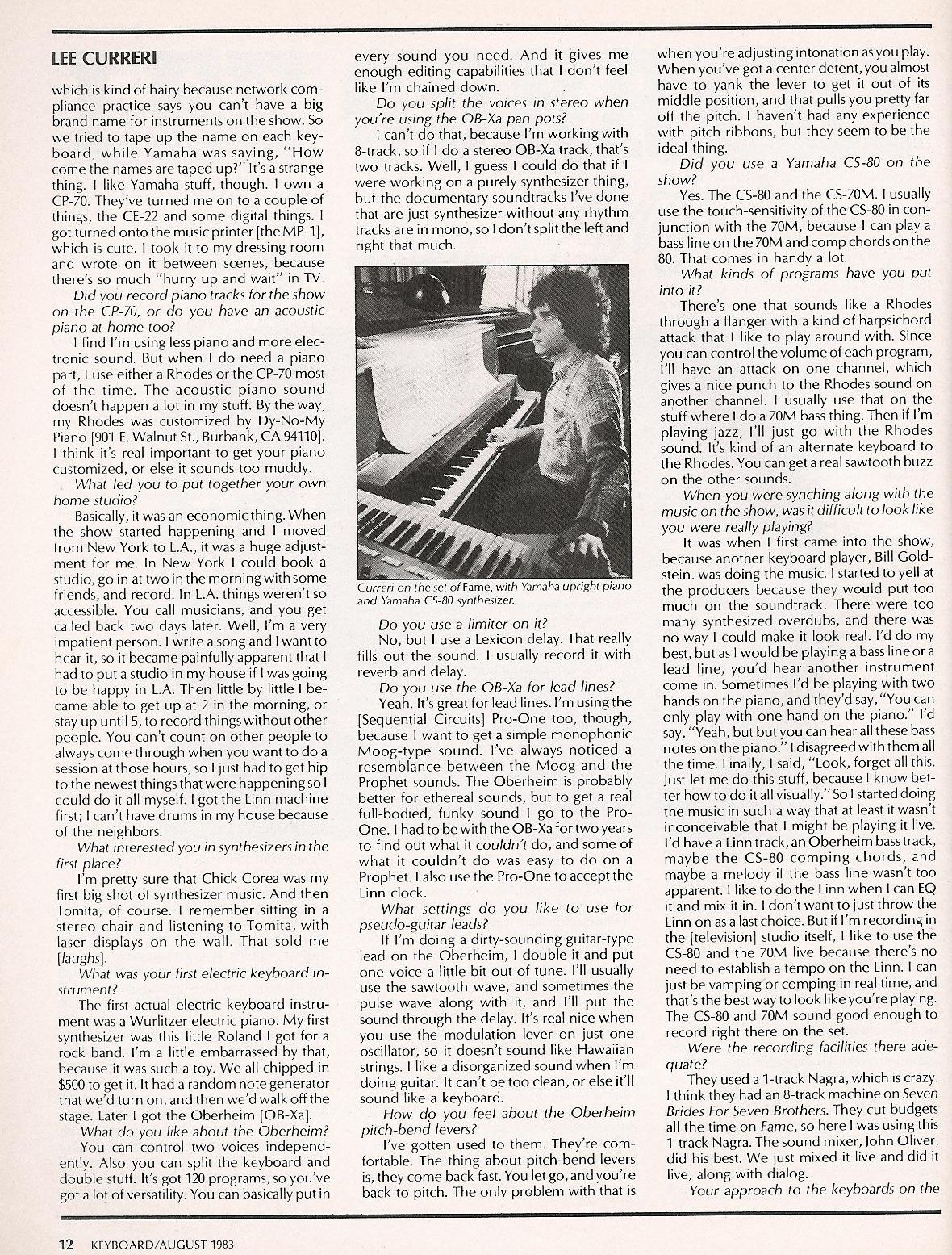

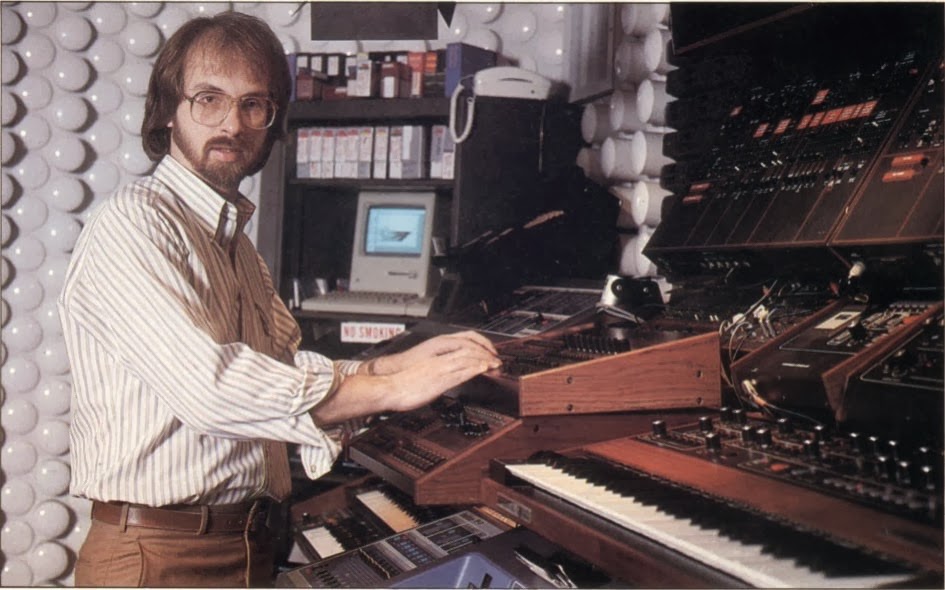

Alan Howarth & his Linn Lm-1

These machines were a huge leap on from the first stand-alone drum machine, the PAiA Programmable Drum Set, which was sold in 1975 as a build-your-own kit. Roger Linn credits Toto drummer Steve Pocaro as the man who first suggested the brainwave of sampling real drums on to a computer chip.

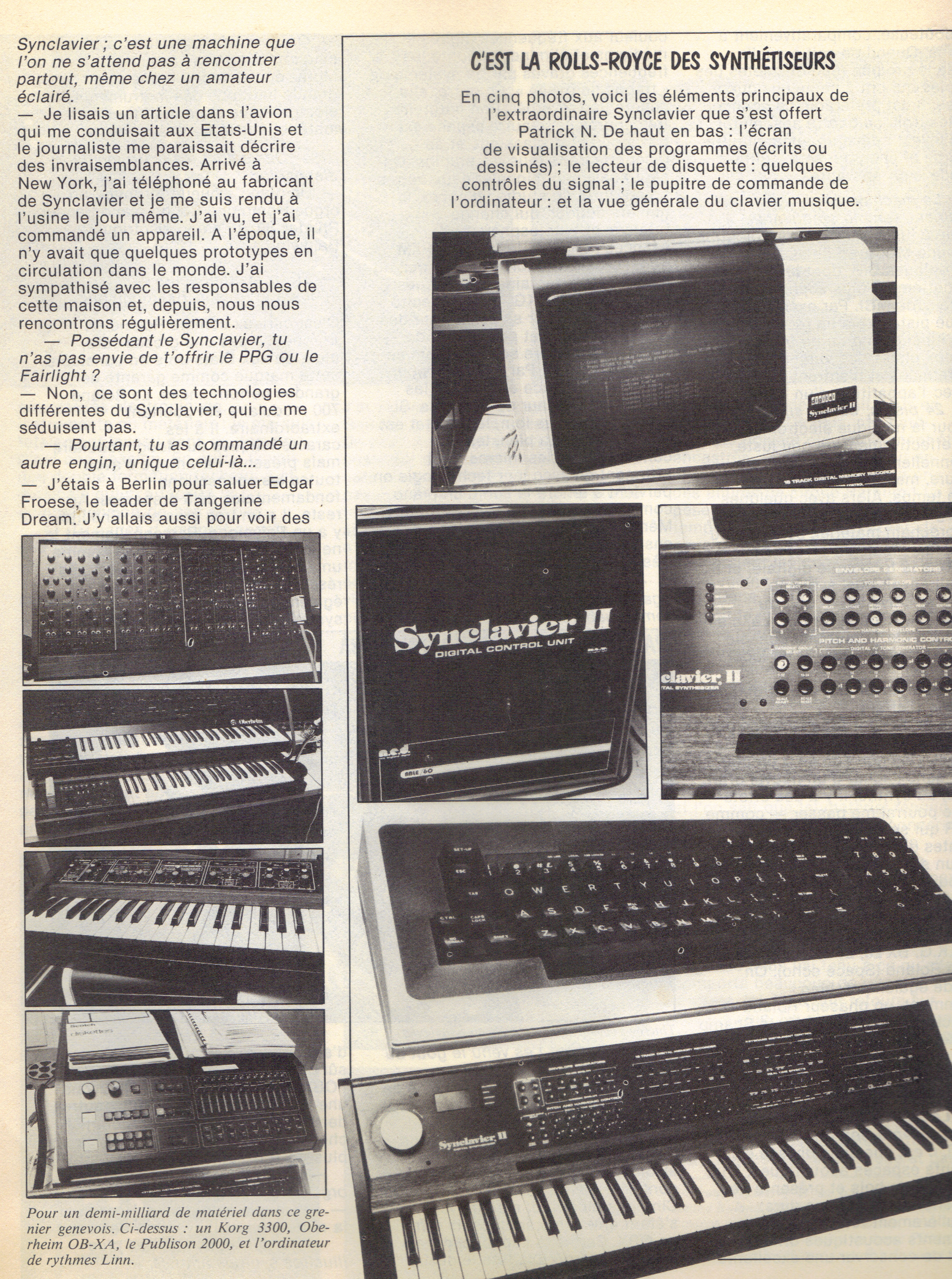

Vangelis & his Linn Lm-1

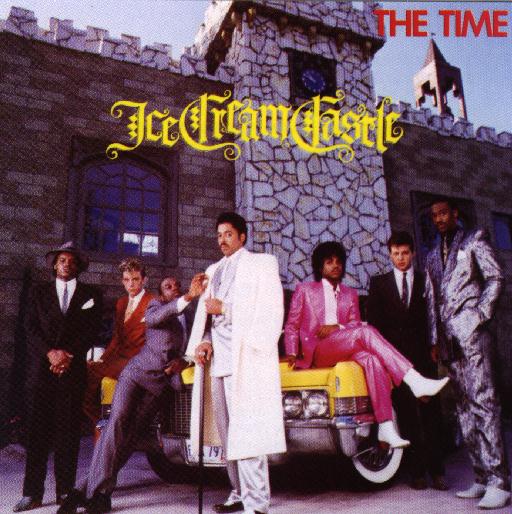

Aficionados regard Prince as some sort of Hendrix of the LM-1; see his The Time classic, 777-9311.

Five facts and things!

Roger Linn has never been able to recall exactly who played the now famous drum hits for the LM-1's samples. Steve Pocaro's brother, Jeff (also of Toto), and Motown session drummer James Gadson have both been suggested as likely candidates.

Originally retailing at a cool $5,500 in 1980, the LM-1 had been replaced by the much cheaper, more stripped-down and error-corrected LinnDrum by 1982. The DMX, in a similar timeframe, was replaced by the simpler Oberheim DX. The new machines were more commercially successful, but lacked the, ahem, "personality" of the erratic, imprecise computer clocks in the original LM-1 and DMX.While the bigger, more "natural" sound of the LM-1 was instantly more attractive to rock musicians than the early analogue drum machines, the Linn machine did have session drummers running scared for a while. This baiting advertisement campaign, with the slogan What the hell is the "kuh" sound

You might see this being hotly debated on forums dedicated to Linn machines. It was Prince's signature trick, a special kind of sound that has proved frustratingly elusive to emulate – kind of the Holy Grail of drum machine noises (and achieved, at least partly, through Prince feeding the Drum Computer through his guitar's Boss pedalboard).

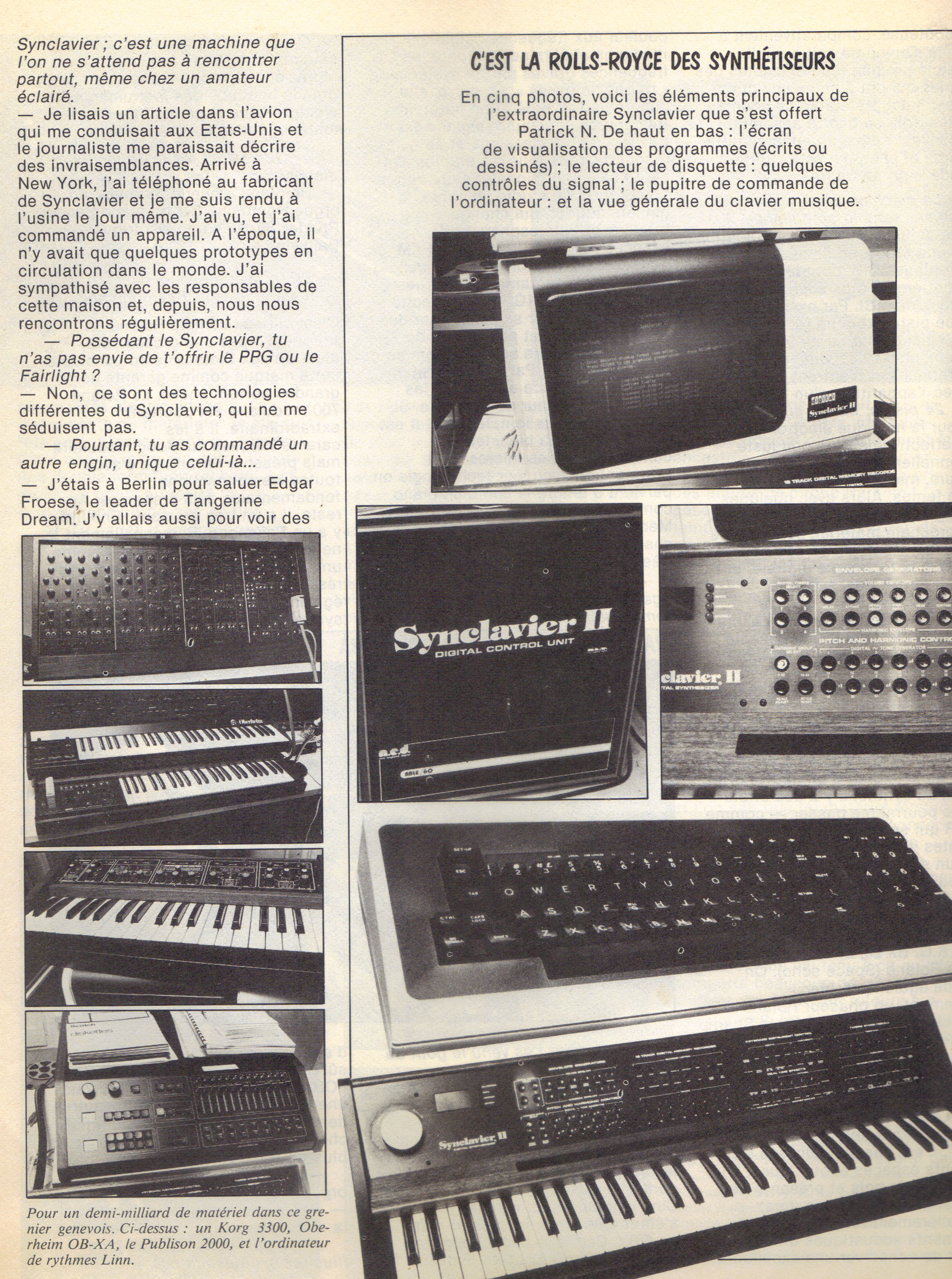

Un classique de la variété française, 100% électronique, joué note par note sur des synthés vintage par Raymond Lefèvre tout seul puis enregistré sur un 16 pistes. Pour le thème mélodique, il s'était inspiré de bourrées auvergnates. En dépit de moyens "petit budget", le résultat est là: un tube énorme , rythmé par une Linn lm-1 extra ordinaire

The Linn Sound: "'I believe the LM-1 sounded better because I didn't incorporate strict textbook digital sampling theory. By the book, I should have filtered out any playback frequencies above the Nyquist frequency, which is a little less that one-half of the sampling frequency. I used a sampling rate of around 27kHz. However, filtering on playback would have made some of the drums sound pretty dull. Instead, I let some of the frequencies above that point get through, because the results - which can get distorted - sounded like the sizzle of drums anyway. Thanks to that decision, the LM-1 sounded better than some drum machines with the same sampling rate, because it had the highs. In a sense, I'm thankful that I wasn't very good at the engineering.'"

The Outs: "Linn realized early on that musicians could get more out of his sampled drum sounds if they were tunable, and if each sound had a separate output, so that they could be routed to different effects processors. Another feature found only on his drum machines is a knob for varying the hi-hat's decay. It was on the LM-1's back panel."

Linn, the salesman: "Even before the LM-1 went into production, Linn was able to drum up (pun intended) buyers. They must have wondered what they were in for, though. 'I had a prototype that wasn't actually producible, basically a cardboard box with a bunch of wire-wrap boards mounted inside. But it worked. I would show it to people who had come over to my house, and they would give me 50% deposits on the finished product. On occasion, I would take this cardboard box down to somebody's session and show it to them. It was pretty hilarious.

"'Later, when I had a real prototype, I'd keep it in my car. At one party, I showed it to some members of Fleetwood Mac, and I generated some sales from that.' ... 'I used to play with Leon Russell, so he bought one. Stevie Wonder bought one of the first ones. Boz Scaggs bought one. So did Daryl Dragon (the Captain), Peter Gabriel.'"

Cymbals?: "If you check out [the] list of LM-1 sounds, you may note that there weren't any cymbals. Bob Easton, whose 360 Systems took over the manufacturing of the LM-1, filled the gap. 'Bob manufactured two cards that he would install into LM-1s to provide cymbal sounds; one card was a crash and the other a ride. Each card had about 32K of memory.'"

So how do we apply this idea of loose, fluid timing to electronic music? The earliest sequencers and drum machines played using completely rigid timing, with evenly spaced gaps in between each division of the bar. Programming was typically achieved via a step sequencer or real-time recording quantised to the nearest 16th note. On the Roland TR-808, for instance, each of the 16 steps in a programmed beat is played with perfectly straight timing.

The ‘swing’ function as we now know it – originally known as ‘shuffle’, a term still used by some hardware manufacturers and software developers – was first introduced in Roger Linn‘s 1979 LM-1 Drum Computer. Linn realised that he could approximate the effect of a human drummer playing in swing timing by quantising each drum beat to the nearest step and then delaying the playback of every other step in the sequencer (to see how Linn introduced his ‘auto-correct’ and ‘shuffle’ features, take a look at the LM-1 manual). But this effect was useful for more than just jazz-style triplet-derived swing timing; different delay times could replicate a variety of lazy, swinging grooves. The longer the delay, the more obvious the effect.

Linn’s system used percentages to express the amount of swing applied to every second step. (At this point let’s assume we’re talking about the most commonly used form of swing in dance music: 16th-note swing.) Those percentages pertain to the degree that every second 16th note is positioned in relation to the beats either side of it. So 50% swing refers to straight timing, where every second step is played exactly half way between the two beats either side of it.

By the mid 80s, this implementation of swing had been adopted by most other manufacturers. Adding swing to a drum beat or to melodic elements can introduce a more human feel to a pattern, but just as importantly, even the smallest amount of swing can enhance a groove in a uniquely and inexplicably appealing way.

Even though MIDI sequencing is now accurate enough to record and replay the nuances of a live MIDI drum performance very precisely, few of us have the accuracy with drum pads to achieve the same effect as quantised beats with swing applied. We could debate the relative merits of ‘real’ human timing versus computer timing for days on end, but it’s missing the point; human timing works well in some cases, but quantised beats and swing are equally valid and at least as effective for most dance music.

ABC Lexicon of Love "The Look of Love", Poison Arrow 1982 ABBA "The Day Before You Came", "Givin' a Little Bit More", "Should I Laugh or Cry", "You Owe Me One", "Under Attack" 1981-1982 Alphaville "Big In Japan", "Sounds Like A Melody" 1984 America View from the Ground "You Can Do Magic" 1982 Aneka Aneka 1981 Bill Wolfer Wolf 1982 Billy Idol Billy Idol "White Wedding (Part 2)", "Hot in the City" 1982 Blancmange Happy Families 1982 Blancmange Believe You Me 1985 Bob James Hands Down "Macumba", "It's Only Me" 1982 Kurtis Blow The Cars Heartbeat City 1984 The Chemical Brothers Dig Your Own Hole "It Doesn't Matter" 1997 David Sanborn Backstreet 1983 Dave Grusin Night Lines "Power Wave", "Thankful N' Thoughtful" (combined with Simmons (electronic drum company)), "Theme From "St.Elsewhere"", "Haunting Me", "Night-Lines", "Tick-Tock", "Kitchen Dance", "Somewhere Between Old And New York" 1984 Def Leppard Pyromania 1983 D.I.M. & Tai "Lyposuct" Devo New Traditionalists 1981 Devo Oh, No! It's Devo 1982 Dionne Warwick Heartbreaker Heartbreaker 1982 Dollar Don Henley I Can't Stand Still "Dirty Laundry" 1982 Eddie Murphy Eddie Murphy "Boogie in Your Butt", "Enough is Enough" 1982 Laurie Anderson Elton John The Fox "Nobody Wins" 1981 F.R. David "Words", "Pick Up The Phone" 1982/83 Falco Einzelhaft "Der Kommissar" 1982 Farley Jackmaster Funk Gay Men "I'm a Man (Who Needs a Man)" 1983 Giorgio Moroder Cat People OST 1982 George Benson "Turn Your Love Around" 1981 Genesis Genesis "Mama" 1983 Gary Low "You Are a Danger" 1982 Gary Numan Dance 1981 Gary Numan I, Assassin 1982 Gary Numan Warriors 1983 Gazebo "Masterpiece" Hall & Oates H2O "Maneater" 1982 Heaven 17 Penthouse and Pavement 1981 Heaven 17 The Luxury Gap 1983 Herbie Hancock Mr.Hands "Textures" 1980 Hooked on Classics Hooked on Classics, Hooked on Classics 2: Can't Stop the Classics, Hooked on Classics 3: Journey Through the Classics 1981-1983 The Human League Dare 1981 The Human League Fascination! 1983 The Human League Hysteria 1984 Icehouse Primitive Man "Great Southern Land", "Hey Little Girl", "Glam" 1982 Joe Esposito "Lady, Lady, Lady" 1983 John Carpenter "Escape From New York", "Halloween II" 1981 John Farnham "You're the Voice" 1986 John Mellencamp "Jack and Diane" 1982 Jon & Vangelis Private Collection 1983 John Foxx 'The Garden' Jean Michel Jarre Arpegiator, Zoolook 1981/82/84 Jeff Lorber It's a Fact "Tierra Verde" 1982 Kenny G Kenny G (album) "The Shuffle" 1982 Lee Ritenour Rit (album) "(Just) Tell Me Pretty Lies", "Countdown (Captain Fingers)", "On The Slow Glide" 1981 Lindsey Buckingham National Lampoon's Vacation: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack "Holiday Road", "Dancin' Across the USA" 1983 Julian Tydelski presents NAILUJ On A Journey "In The City", "Bring Me Up", "Afterhours" 2010 Mahlathini and the Mahotella Queens Matthew Friedberger "Holy Ghost Language School/Winter Women" Men Without Hats Rhythm of Youth 1982 Michael Jackson Thriller "Wanna Be Startin' Somethin'", "Baby Be Mine", "Thriller", "Human Nature" 1982 Mark Knopfler Going Home (Theme from Local Hero) 1983 Mike Oldfield Five Miles Out 1982 Mtume Juicy Fruit Juicy Fruit 1983 Neil Young Trans 1982 Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark P. Lion Springtime "Kings of the Night" 1984 Paul Davis Cool Night 1981 Paul McCartney Tug of War "What's That You're Doing?" 1982 Paul McCartney Pipes of Peace "The Other Me" 1983 Peter Gabriel Security 1982 Prince 1999, Purple Rain, Around the World in a Day, Parade and Sign o' the Times I Would Die 4 U, Baby I'm A Star 1982-1984 Pete Shelley Homosapien, XL1 1981/83 Reading Rainbow Songs from Reading Rainbow 1984 Ric Ocasek Beatitude Rod Stewart Tonight I'm Yours "Young Turks", "Tonight I'm Yours" 1981 Roxy Music Avalon 1982 Ryan Paris Secret Service Cutting Corners "Flash in the Night", "The Dancer" 1982 Sheila E. The Glamorous Life 1984 Sipho Mabuse Afrodizzia "Shikisha" 1986 Steve Hackett Cured 1981 Sparks Angst in My Pants "I Predict" 1982 Sparks "Modesty Plays" 1983 Steve Winwood Talking Back to the Night "Valerie", "Talking Back to the Night" 1982 Tight Fit Tight Fit "The Lion Sleeps Tonight" 1982 Toto Coelo Man o' War 1982 The Emotions Sincerely "Are You Through With My Heart", "Sincerely" 1984 The Time "777-9311", "Jungle Love" 1982-84 Thompson Twins Todd Rundgren Ultravox Quartet "We Came to Dance" 1982 Vangelis State of Independence (with Donna Summer) 1982 Vanity Wild Animal 1984 Vanity 6 "Nasty Girl" 1982 Wang Chung Points on the Curve Superfunk the band france2013

The first drum machines to feature digital sampling. Before the release of Linn's LM-1 Drum Computer in 1980, early drum machines could only synthesise drum sounds out of bursts of white noise or sine waves. The LM-1 and Oberheim's DMX sampled actual drum hits, which could be programmed and manipulated with lovely knobs.

The LM-1 was elite gear. Only 525 machines were ever made, and inventor Roger Linn managed to flog them by dragging around a little cardboard-box prototype to showbiz parties. Notching up pre-orders with Peter Gabriel, Fleetwood Mac and Stevie Wonder, the Drum Computer became a bourgeois must-have object, and was quickly put to use in hit records from the Human League, Gary Numan, and, most notably, Prince. The DMX, released a year later, became synonymous with booming hip-hop: producer Davy DMX loved the machine so much he not only named himself after it (along with DMX Krew and, of course, DMX), but he built Run DMC's whole sound around it. Check out these Spotify playlists for the DMX and the LM-1.

The Linn stored twelve 8-bit samples, which could be individually tuned: kick, snare, hi-hat, cabassa, tambourine, two toms, two congas, cowbell, clave and handclap (but no cymbals!). The DMX boasted 24 drum sounds and a bunch of pseudo-humanising gimmicks such as rolls and "flams", as well as a pre-MIDI synchronisation doohicky.

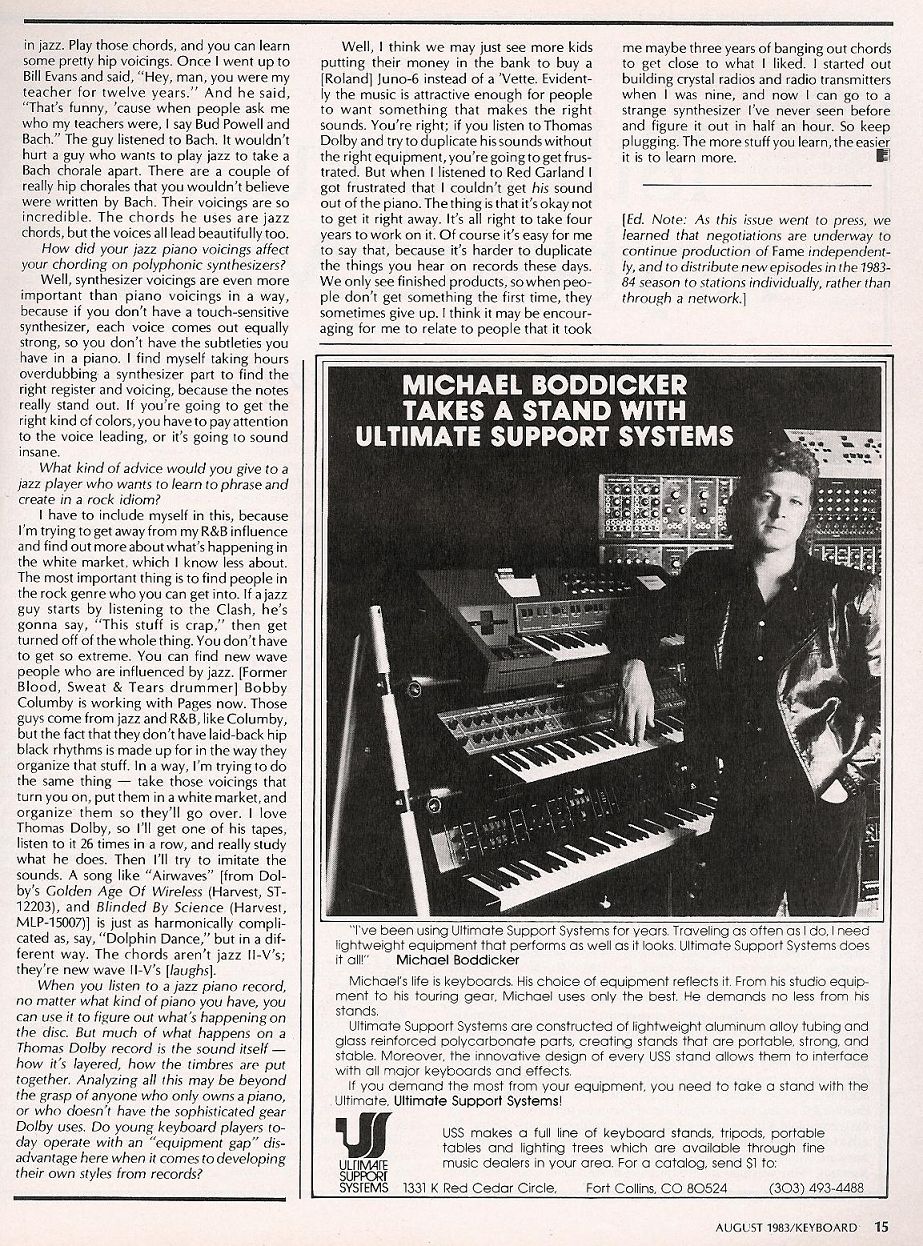

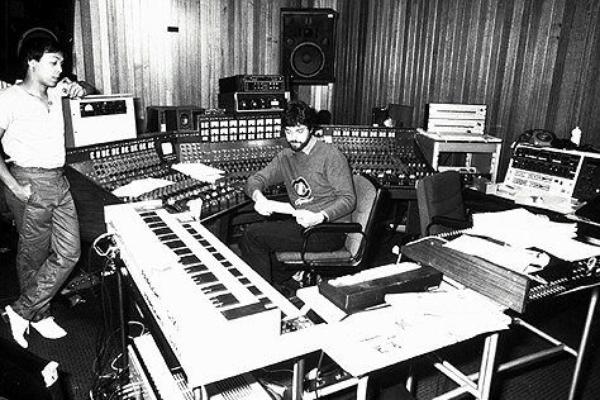

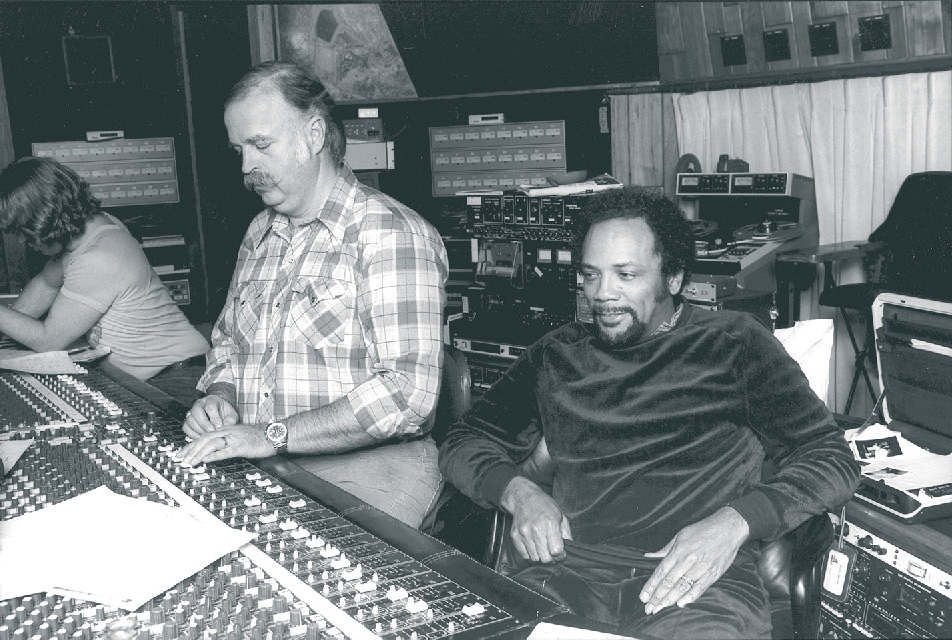

Michael with Bill Wolfer.

Michael Jackson’s fans know you more particularly for your amazing synthesizer play on several famous tracks like « Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’ », « Beat It » or « Billie Jean ». First of all, could you please tell us more about your career as a musician?

I’ve been playing professionally since the age of fifteen, starting in my hometown of Cheyenne, Wyoming. I studied music at the University of Wyoming and Berklee College of Music in Boston. After moving to Los Angeles in 1978, I began doing studio work, mostly programming synthesizers at first, and later as a player as well. Eventually, I became a producer and songwriter, and recorded albums as an artist as well. Co-writing and producing Shalamar’s « Dancing in the Sheets » from the « Footloose » soundtrack earned me two Grammy nominations.

You’ve met Michael Jackson exactly at the time of his artistic emancipation. You’ve also shared the stage with him and his brothers on the Thriumph Tour. What do you recall of that period ?

The first time I met Michael and his brothers was when they were recording the Triumph album. My friend Ronnie Foster had been called to do some keyboard parts, and he asked them to include me to program the synthesizers. They must have noticed that I could play as well as program, and the next week they called me in to play overdubs on « Can You Feel It. » Michael wanted an effect that fades in and builds to a crescendo, sounding almost as if it were played backwards. It makes it’s first appearance at 3:14 on the song. It was done on a Yamaha CS-80, a massive 220 pound beast of a synthesizer. For some reason, I wasn’t listed on the credits when the album appeared, but that is me on there!

About a year later, in 1981, my friend Jonathan Moffet told me that the Jacksons were auditioning for a keyboard player, and I jumped at the chance, and got the gig. We rehearsed for six weeks, starting in a rehearsal hall in the valley, moving to a large sound stage in Hollywood for the final dress rehearsals. The rehearsals were fun, and six weeks was quite a luxury–it gave us plenty of time to get comfortable with the songs, and gave us all an opportunity to get to know each other. Michael and his brothers had a good work ethic, they knew what they wanted, but it never felt pressured or tense–it was always a very relaxed atmosphere.

Of course, I knew of them from their early days as the Jackson Five, and I was a fan of that era as well as the Destiny and Triumph albums. But I really had no idea how popular they were, especially Michael. I was quite unprepared when 6,000 fans were waiting for us at the airport in Memphis for the first gig. We literally had to run through the airport, chased by screaming fans into waiting limos. It was like something out of It’s a Hard Day’s Night! The next three months we worked our way across the country, playing large arenas in all the major cities, including two nights in New York at Madison Square Garden. The tour ended with three nights at the Los Angeles Forum, and the end-of-tour party on the last night was packed with celebrities, including Quincy Jones, Steven Spielberg, Stevie Wonder, Magic Johnson, Prince and others.

On the Thriumph Tour, you have adapted songs from « Destiny », « Triumph » and Off The Wall ». Each of these albums had a particular sound. How difficult was the adaptation of these musical studio works for the stage ?

It was easier for most of the musicians than it was for me. The bass player is going to play the bass part, the drummer the drum part, and so forth, but those albums had so many synth and keyboard overdubs that it was impossible to incorporate all of them, even with both Randy and I playing keyboards. And Randy wasn’t always playing, he did choreography with the brothers, or played congas at times. We had to pick the important parts to emphasize, plus I had to cover any string parts. It kept me busy! My keyboard setup was in a « U » shape with five instruments. On my left was a Fender Rhodes piano with a Mini-moog on top of it. In the center was a Yamaha CP-70 electric-acoustic piano with a Prophet-5 synth on top, and on my right was the giant Yamaha CS-80.

How were born live versions of the songs like « Lovely One » or « Working Day And Night » ?

Well, with an act like The Jacksons, the main thing is to sound as close to the record as possible, that’s what the fans expect. At the same time, there are lots of ways to incorporate a few twists, or surprises, or ways to extend a song. On « Lovely One, » it was just a matter of getting that groove happening, and then there was a break added, and a breakdown to just drums and vocals, with call and response between Michael and the brothers. « Working Day and Night » has extended breakdowns to feature solos from Tito’s guitar and Randy’s congas, and culminates with a magic trick that involved Michael disappearing and then re-appearing on another part of the stage, with a costume change, and a deafeningly-loud pyrotechnic explosion. Michael loved that explosion, and always asked the pyro technician to make it louder. I do believe that we violated the fire codes every night with that thing.

Who gave the instructions, guidelines, ideas in order to adapt songs for the stage ?

It was a collaboration, but of course the brothers were in charge. The musicians were responsible for learning the songs from the records, and then we’d rehearse them. Once, Jackie asked me to play an obscure synth part on one of the songs, I don’t remember which one. I told him that if I did that part, I wouldn’t be able to play the main part. Jackie insisted I play it. When we were rehearsing it, Michael stopped the band and asked me why I wasn’t playing the main keyboard part. I told him that Jackie wanted me to play this other part. Michael told his brothers, « We need a meeting. » They left to another room, and when they came back, Michael told me to go back to playing the main part. And that was always how it went, anytime there was a disagreement between them. They would always go discuss it in private, so they represented a united front. I respected that.

In 1982, on your first solo album « Wolf » (Constellation Records) Michael Jackson is mentioned on the track credits of « Papa Was A Rolling Stone » and « So Shy ». When listening to the tracks, due to mixing work, Michael’s voice isn’t directly recognizable. Could you explain us your musical choices?

Since it was the first solo album by an unknown, I certainly wasn’t shy about asking a few of my friends to help out. Michael and I got to the point where we got along very well, and we respected each other, and enjoyed each other’s company. I didn’t know if he would do it, but I thought, why not ask? I was delighted that he immediately accepted. And I never intended for his voice to be recognizable, I just wanted him to fill out the background vocals, adding a fourth voice to the great family group, The Waters. If I had tried for some sort of solo thing from him, then it would have been complicated. But it was a classic Motown song, and he was from that era.

Could you share with us your experiences in studio with Michael during the recording of these songs?

I hadn’t told The Waters anything other than I had invited someone to sing with them. I didn’t want them to be disappointed if for some reason Michael couldn’t make it. But he did, right on time, and you should have seen their faces when they saw who was going to be singing with them! Michael loved doing the session. He loved being in the studio, and working, and it was fun for him to just be a studio singer for the day. No pressure, just sing, blend in with the group, and be professional, and he had fun doing that. They knocked it out so fast, that Michael was disappointed that it was over, and asked if I had anything else they could sing on. I told the engineer to put « So Shy » on the machine, and we did that in no time. It was a fun, relaxed session.

On the same year, you’ve worked on the Diana Ross « Silk Electrik » album and more particularly on « Muscles ». Could you please tell us more about your feelings about working with Diana Ross, anecdotes with Diana and Michael during this session, the recording work and stages of the creation process ?Michael called me, told me he was producing a song for Diana Ross, and could I come play some synthesizer. Of course, I was happy to do it, I’d been a fan of hers from way back. Sadly, she wasn’t at the studio that day. It was Michael and I, the engineers, and Michael’s assistant, Nelson Hayes, and Muscles, Michael’s enormous boa constrictor. Yes, the song was inspired by, and named for his pet snake. For most of the session, Muscles was sleeping in this big pillow case, but then Michael got him out, and asked me if I wanted to hold him. This snake was so big and heavy, it took both Michael and Nelson to lift it up and drape it around my shoulders. It must have weighed close to seventy pounds. After a minute, the snake started squeezing my neck, getting a tighter grip on me. I told Michael, « Get this thing off of me! » They laughed, and took him off. They thought it was very funny, I wasn’t so sure.

As far as the work that day, I was coming in after the basic tracks had been laid, and overdubbing some synthesizer parts. As always, it was fun to work with Michael, but I remember that snake more than anything else.

On « Muscles », you’ve worked with Jonathan Moffet who was also by your side during the Triumph Tour. What’s the difference between working in studio and the collaboration you had with him on stage ?

Jonathan wasn’t in the studio that day, he had done the drums at an earlier session. But I have worked with him many times in the studio, and just as he is on stage, he is rock solid, a great drummer, and was one of my best friends on the tour. He’s a great guy.

You’ve also worked on « Say Say Say », an unforgettable duet shared by Paul McCartney & Michael Jackson on « Pipes of peace » (1983). Could tell us about your work on this song ?

Michael called to ask if I would help with a demo. I said sure, do you want me to come over to your house? He said, no, can we do it at yours? I was surprised that he would come to me, but why not? Maybe he wanted to get out of the house. When he came over, my wife was watching a re-run of « Grease » on TV. Michael flopped on the couch, saying, « I love this movie! » After it was over, he took out a cassette, and it was only then that I learned that it was a song that he and Paul McCartney had written. Michael wanted to do an elaborate demo to show Paul his vision of the song. The cassette was just Paul on acoustic guitar, and he and Michael singing. We worked out the beat on a Linn LM-1 drum machine,

and recorded a basic demo of Rhodes piano, synth bass and the drum machine on my four track recorder. This was used a few days later in the studio to teach the song to Nate Watts (bass) and Ricky Lawson (drums). We laid down the track, just the three of us, and then David Williams did guitar overdubs. Later that week, I came in to do some synth overdubs, and watched him record the horns and harmonica solo.

It was pretty elaborate for a demo! Michael confided in me that he was doing a full 24 track recording in the hope that Paul would just use his version, adding their vocals and mixing it. Months later, Michael told me the story. He had flown to England, and played the demo for Paul. Paul immediately heard the sound quality, and asked, « Is this 24 track? » Michael said it was. Paul said, « Did you bring it with you? » And, of course he had. So, the ‘demo’ became the record, just as Michael had hoped.

I regret that I never got to meet Paul, as he is one of my heroes, but after the album was released, Paul sent all of the musicians specially engraved pewter medals, along with a certificate and a personally signed album. It was such a cool gesture, so far beyond the typical platinum album award. It hangs on my wall today, one of my most treasured items.

On the « Thriller » album, you took part on the amazing music part of « Billie Jean ». You played synthesizer on the most famous track in world of music ! What’s your personal feeling ?

It is the most famous track, but that keyboard part, those three chords, that sound, has got to be the most iconic keyboard part in recent history. I say that in all humility, because anyone could have played it, it’s certainly not technically demanding. And because that song was so successful, practically everyone on the Planet Earth has heard me play! It’s strange to think about in that way, but true. I am proud of the sound that I programmed. Anyone could have played the part, but the reason Michael called me was that he had heard me fooling around with that sound when we were on tour, and he remembered it, and made a note of it in his mind for use in Billie Jean. The sound is a Yamaha CS-80 again. It is definitely my favorite synthesizer–I still have one. No, it’s not the one used on the record, that was a rental.

Could you also share with us technical specificities used on « Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’ » and « Beat It » ?

With those two songs my role was more subtle. There are a lot of synthesizers on those songs–textures, atmospheric stuff–we call those sounds ‘pads.’ Quincy called it « ear candy. » On Beat It, for example, around 2:20 you hear what sounds like a synthesized choir–that me on a Roland Jupiter 8. Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’ is similar, synth pads that come and go, more of a string sound this time, reinforcing the basic chords. I was glad to hear The Waters singing with Michael again. Apparently, I wasn’t the only one who thought they sounded good together!

Could you tell us more about your experience in studio when this album was recorded ?

Billie Jean started out at Michael’s house in Encino. He had turned the guest house into a 16 track studio, and we made demos there of the three songs that I eventually recorded with Quincy for the album. Michael and I started by sitting down at a Rhodes piano, and Michael sang me the bass line. I started playing it, and then he sang the top notes of the three chords that ascend and descend over that ostinato bass. At that point, we spent maybe an hour or more trying out different harmonies for the rest of the chords. There are a million ways you can harmonize those notes, and I tried them all before I landed on the one he was looking for. The amazing part about that is that, to me, several of the combinations I tried sounded very hip to me–they worked, but Michael never lost sight of what he had been hearing in his head. He didn’t play an instrument, but he was definitely a musician. He could work out entire arrangements in his head, and hang onto them, even when he was hearing something very close.

The next step was recreating the sound Michael had heard me experimenting with sometime during the tour. I didn’t even remember it at first. There was a CS-80 there, and eventually I remembered a sound where I was trying to get something like French horns and strings simultaneously, but this other weird aspect, almost like human voices crept in. Once I had the sound programmed, we recorded the demo.

I will always remember the day I recorded that part at Westlake Studios. Michael and Quincy were working on a deadline for a children’s album about E.T. the Extraterrestrial in Studio A. Michael showed me to Studio B, where a CS-80 was setup. He said, « you know the part, go ahead and record it, and I’ll come listen later. » So it was just me and the second engineer Matt. After I had programmed the sound, I got Michael to come listen before we actually recorded it. He approved, and we recorded the part.

Do you have anecdotes with Michael or Quincy jones ?

Here’s a Michael story: Once, when we were recording the demos for Thriller in Encino, we took a break. Michael had this big ornate bird cage in the studio with a big cockatoo in it. He grabbed some bird seed, and went outside on the front steps, where I had gone to have a cigarette. He raised his hand to the sky with the bird seed in his open palm, and stood there like a statue. I thought he had lost his mind, what’s he doing? After just a few minutes, this enormous wild blue jay came swooping out of a tree on the other side of the yard, landed on his hand, and ate the seed. He really was like a Disney character in some ways.

Quincy was great, always great. One of the finest people in the music industry. He made everyone feel so relaxed, and the atmosphere in the studio was always fun. About a year after I had done the Thriller sessions, my wife and I were at a screening in Westwood when I saw Quincy across the lobby. I wanted to introduce him to my wife, so we approached him. In my mind, I thought I would need to remind him of my name, but as soon as he saw us, he said, « Bill! How you doing? » I wouldn’t have remembered me, and I don’t meet half the people that Quincy does. He is such a cool guy, and so talented.

More than 30 years after, what’s your vision on your work on the « Thriller » album ?

I’m very proud to have been a small part of it. And my favorite songs on that album are the ones I played on–not because of my involvement, but to me, those are the three songs that really belong to Michael, it’s the beginning of finding his own voice as a writer and arranger, the start of what later became his independence from Quincy. Quincy Jones is THE producer of my time, but Michael was developing his ideas so fully that it made sense for him to produce himself.

You’ve also worked with Stevie Wonder, could tell us more about your collaborations ?

I worked with Stevie as a synth programmer for about two and a half years. It was during that time that I learned about producing, and especially writing. I learned more from being around him, his studio, and his musicians than I did studying music in college. I call it The University of Stevie Wonder. Stevie and I quickly became friends, and he was always kind enough to listen to demos of songs I was writing. Looking back, some of them were really bad, but he always found something positive to say. It was after the Jacksons tour that I was doing more serious demos for what became my first album. I played it for Stevie, and he said I should play it for his attorney, Johannan Vigoda. That had never happened before. Vigoda liked it, played it for Dick Griffey at Solar Records, and I had a record deal. Not bad for a guy from Wyoming. Stevie and I are still friends–I don’t get to see him as often as I would like, but when we get together, it’s like old times. I wouldn’t have had much of a career without him.

I started working with him when he was recording Journey Through The Secret Life of Plants. The electronic drums on the track « Race Babbling » is similar to something I had done on a tape he heard. It involves hooking up several synthesizers to two or three synchronized sequencers. Each synth is programmed as a separate drum part; an Arp 2600 for the bass drum, for example. This was a few years before MIDI and programmable drum machines. All in all, there would be six or seven synthesizers hooked up to the Arp sequencers. It was an elaborate way to create electronic drums. I also worked on Hotter Than July–the complex sounds on « Happy Birthday » is a Prophet 10 synth being fed the rhythms of a drum machine through a vocoder. We also worked on the very first samplers around that time. He had one that was custom built using an Arp 2600 interfaced with a DEC Mini-computer. It could only record a very grainy sample of about 1.5 seconds, and there was no way to store the sound, you had to record it then, because when you turned it off, the sound was gone. Later, he bought a Fairlight CMI, the first one in the States, I believe, and I learned to use that. I went on his Secret Life of Plants tour to make sure that Fairlight was up and running, changing the sounds that were stored on giant eight inch floppy discs.

What’s your opinion on the fact that vocoders and synthesizers from the 80’s are coming back in the last few years ?

It’s a testament to how good they sound. We were too quick to abandon them to digital synthesizers in the 80’s, but at the time, they were very exciting, and it was important to stay current. The capabilities of today’s computer-based samplers and synths are light years beyond what we were working with then, but they lack the warmth of the old analog machines I still have my Mini-moog that I bought in 1972, and it still sounds great. Same goes for my CS-80. The old analog synthesizers were not just innovative, they were great musical instruments.

What’s your actual artistic activities ?

I later became interested in Cuban music, not just the traditional, but the current dance music known as Timba. In 2000, I went to Havana for the first time just to take piano lessons, and learn about the music. Two years later, I was recording with some of the top musicians on the island, and the two albums I recorded there with my group Mamborama were nominated for Cubadisco, Cuba’s equivalent to the Grammy. I more or less lived in Havana for almost three years, it was an amazing time. These days, I am waiting for inspiration. It may turn out to be Waiting For Godot. The music business and the music popular now are both strangers to me. It’s fine, pop music is a young person’s game, and I am 61 now. I’ll always be proud of what I accomplished.

Here’s a Michael story: Once, when we were recording the demos for Thriller in Encino, we took a break. Michael had this big ornate bird cage in the studio with a big cockatoo in it. He grabbed some bird seed, and went outside on the front steps, where I had gone to have a cigarette. He raised his hand to the sky with the bird seed in his open palm, and stood there like a statue. I thought he had lost his mind, what’s he doing? After just a few minutes, this enormous wild blue jay came swooping out of a tree on the other side of the yard, landed on his hand, and ate the seed. He really was like a Disney character in some ways.

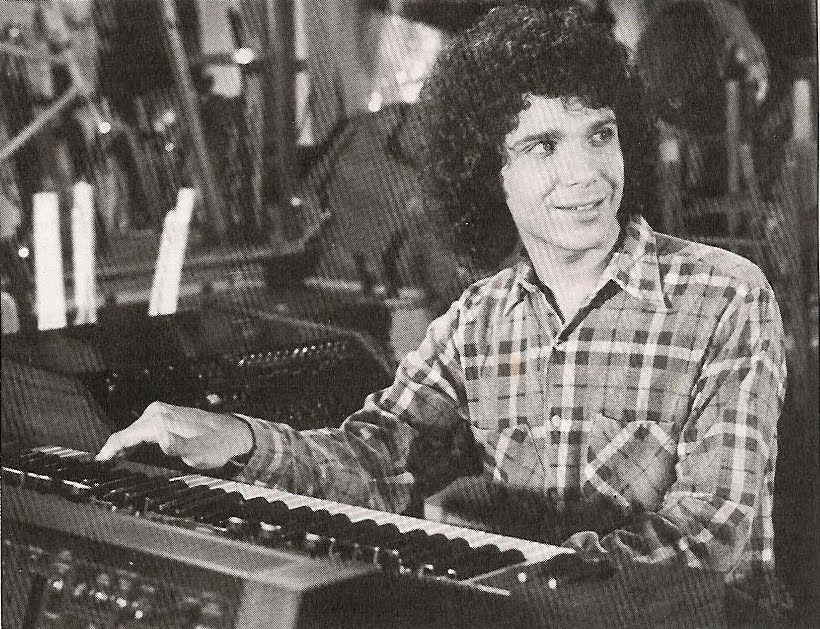

Bill Wolfer, keyboardist who worked on the album Thriller.

Expect from Katherine Jackson’s book “My Family, The Jacksons:

"There was one “pet” that adopted Michael. One day he was eating a pecan in the yard when a blue jay swooped down and took the nut out of his hand! Michael couldn’t believe it so he ran into the house for more pecans, held them out, and “Jay” grabbed them, too. From then on Michael and Jay were friends, and Michael would show him off to guests”.

Right! This is it! Introducing the LM-1 from Linn Electronics. This sophisticated, yet easy to operate machine, contains actual drum sounds recorded digitally in its computer memory. It holds up to 100 drumbeats and these are programmable in real time. Drums include snare, bass, hi-hat, cabasa, tambourine, two congas, two tom-toms, cowbell, clave and hand claps. Programming features include automatic error correction, programmable dynamics, flams, rolls, build-ups, open and closed hi-hat, etc. Special timing circuitry is included to give a 'human' feel to the drumming and all time signatures are possible (including the one our drummer plays after a bottle of rye and a Pepsi).

The LM-1 has versatile editing facilities and rhythm patterns can be linked together into complete song formats. All programmed parts can be retained in the memory when power is switched off and programmed data can be stored on cassette. Other features include a 13 output stereo mixer with volume, pan and separate outputs for each drum. The pitch of each drum can be individually adjusted and the unit can be used to overdub on tape and sync to almost anything.

The bad news is the price — $5,500. Not too expensive, really, when you consider the flexibility of the unit but possibly other manufacturers will see a market here and introduce their own models. It doesn't look quite as pretty as Jane Fonda but then if looks were important our drummer would be peeling potatoes. This is certainly a unit to look at, especially for electronic music composers and enthusiasts. Warren Cann of Ultravox is reviewing this for us.

The music on “Wildstyle”, is credited to a German band called Wunderverke. Here is a picture of them in the studio.

Based on a poorly translated anecdote on the bands site (see above) of the songs recording, it seems as though the track was recorded at the band’s studio in Germany and received a luke warm reception that night from Afrika Bambaataa who took the tapes back to NYC where they were then overdubbed with a vocal track that features Beeside, Zekri’s girlfriend at the time, among others. The track credits Bam and Zekri with the production. It’s interesting to note that the track seems to have featured some sort of an electronic instrument of the band’s own invention.

Here is a historical excerpt from the band’s google-translated website that refers to the devices inception:

“…. the Mr. Franz Knüttel would have been continuously frustrated. As hobby Drummer it always came after one hour of continuous whirling because of lack of concentration from the clock. Thus the question emerged, why there is actually still no machine, to which solch´menschiche weaknesses do not wear anything and which swots precisely nonstop. Answer: Because it is not yet invented!